Part 2 – Disulfiram, GLP-1 agonists

This is part 2 of a brief review of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of alcohol use disorder covering disulfiram and the GLP–1 agents. Much of the information on GLP-1 agonists was presented in more detail in earlier posts here and here.

Disulfiram (Antabuse) is the oldest medication used in the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD). The primary activity is on the metabolism of ethanol in the liver. Ethanol is metabolized in two steps. The first converts ethanol to acetaldehyde by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase. The second step converts acetaldehyde to acetate by the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase.

Disulfiram interferes with this second step preventing metabolism if acetaldehyde. When this product builds up a number of reactions occur. These include flushing, nausea, abdominal cramps, increased heart rate and increased blood pressure.

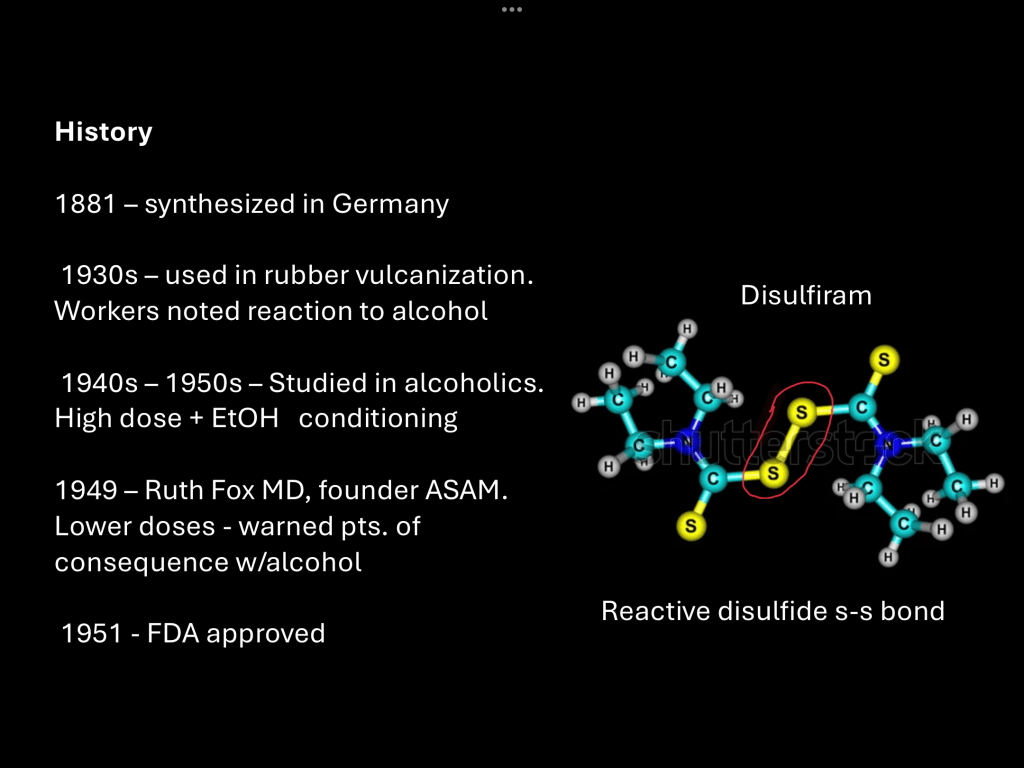

Disulfiram has an interesting history. It was first synthesized by German chemists in 1881. By the 1930s it found a use in industrial vulcanization of rubber. Around that time reports began to emerge that factory workers in the rubber industry began to complain of an intolerance for alcohol.

Further investigation found that disulfiram was the cause of the reaction and it was adapted for use in the treatment of alcohol addiction. Early treatment was based on behavioral aversion and consisted of large doses of oral disulfiram and alcohol. This procedure sometimes resulted in dangerous reactions and some deaths were reported.

In 1949 Ruth Fox, a psychiatrist who had taken an interest in the treatment of alcohol addiction published her results using disulfiram in smaller daily doses while informing patients of what they could expect if they consumed alcohol while taking the medication. This resulted in improved outcomes and safety.

Biological activity of disulfiram is not specific to inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase. In initiating therapy consideration also must include the potential effects of alcohol reaction if the patient does drink.

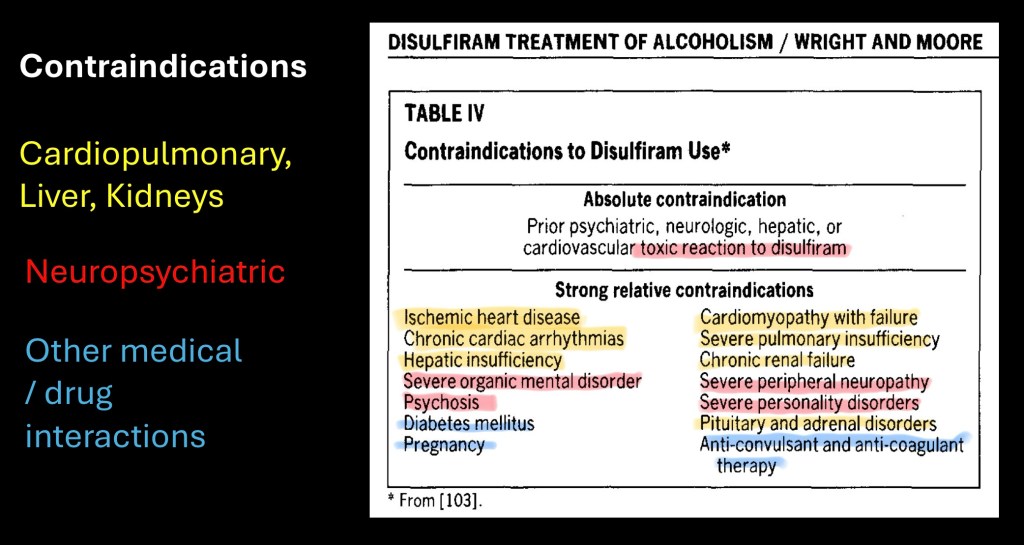

Because of these considerations there are a number if contraindications to disulfiram therapy. In the table above these are grouped into cardiopulmonary and organ dysfunction, neuropsychiatric conditions, and drug interactions along with pregnancy and diabetes.

This is taken from a meta analysis published in 2014. The authors noted a number of studies indicating no significant change from placebo in double-blind placebo controlled trials. They hypothesized that the mechanism of action in disulfiram therapy required knowledge of the potential effects if alcohol is consumed. They thought that double blind studies were therefore less representative than open label studies.

The table above shows the relative effectiveness of controls vs disulfiram for blinded vs open label studies (Hodges G). The vertical red line is the point where placebo and disulfiram effects are equal. Points to the right favor disulfiram and to the left controls. Horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Above the red line composite blinded studies demonstrate no benefit of disulfiram for abstinence outcomes. Below there is clear benefit of disulfiram in open label studies.

Potential use in treatment of cocaine use disorder has been investigated. Above diagram illustrates a potential mechanism. In the breakdown of dopamine to inactive components another variation of aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH-2 is an intermediate step. Disulfiram inhibits this reaction raising levels of synaptic dopamine.

Cocaine acts by blocking dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake resulting it its strong reinforcing effects. This is less prominent when baseline levels are high.

This study combined disulfiram with two types of psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral and interpersonal therapy. The subjects were then subdivided to receive either daily disulfiram or placebo.

Average daily self reported cocaine use was recorded for the four groups shown above. A significant decrease in consumption was demonstrated for disulfiram subjects irrespective of the type of psychotherapy.

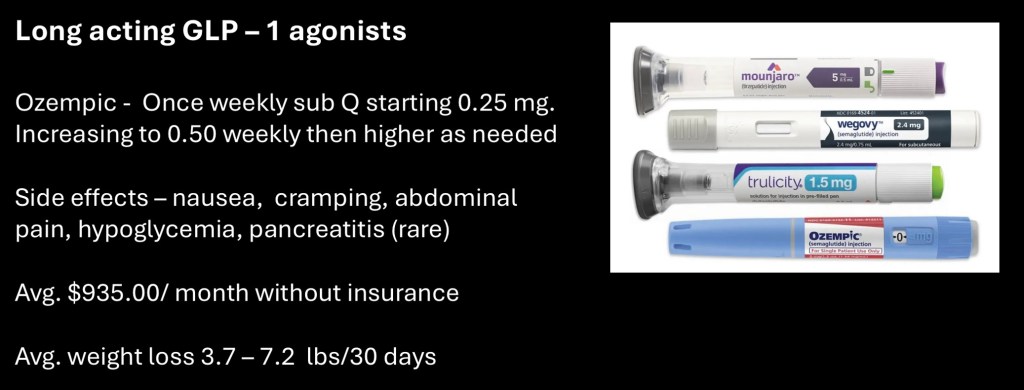

There are several formulations of GLP-1 agonists commercially available. They are provided in prefilled syringes suitable for self injection. The once per week dose is most often titrated up over a period of weeks to months to the desired effect.

Adverse effects include nausea, abdominal cramping, and hypoglycemia. Pancreatitis is a rare complication.

Cost is a significant issue with a one month supply ranging to $935.00.

For weight loss between 3.2 to 5.7 lbs/month loss can be obtained.

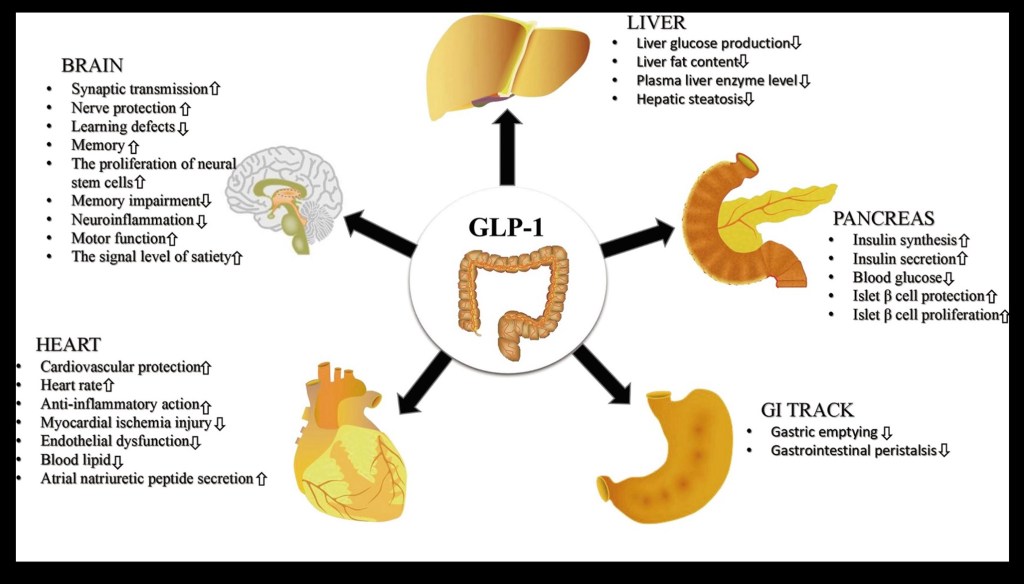

GLP stands for Glucagon Like Peptide. It is a hormone made in the small intestine. The diagram shows how this works. As food products move through the first part of the small intestine “L”cells recognize the glucose passing through. This initiates a cascade of reactions resulting in release of GLP-1 into the bloodstream from which it travels to the pancreas and other organs. In the pancreas it activates islet cells producing insulin. It also prevents glucose production in the liver. The effect lowers blood sugar.

GLP-1 is a peptide, a small string of amino acids. It degrades quickly in the range of minutes after it is released. While it has been known about for some time the short duration of action has made it impractical for clinical use.

The innovation came when researchers were able to synthesize longer lasting analogues activating GLP receptors. Injectable agents can be given once weekly. Oral agents are currently undergoing clinical trials.

New uses have come to light since the GLP-1 medications came into clinical use. It is likely that the full potential was not suspected during investigation of the short acting native hormone.

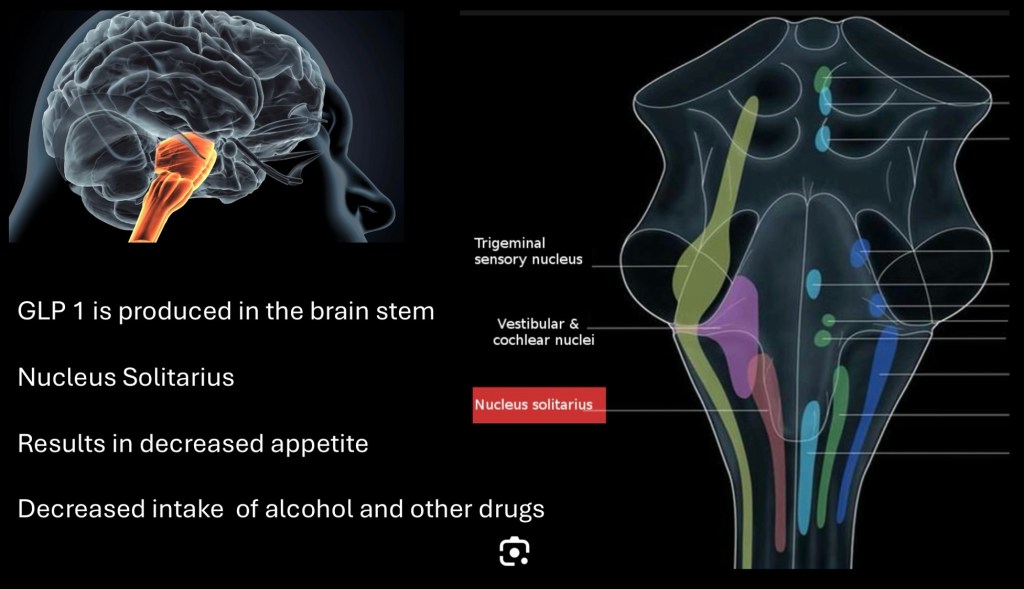

Reports from patients of unintentional decreased desire for and consumption of alcohol has led to further investigation into possible treatment for substance use disorders.

A second site of GLP-1 production has been found in the nucleus Solitarius in the brain stem. The full extent of this pathway is not completely understood but it does connect to the reward pathway and areas involved in hunger and satiety.

A number of clinical trials on using GLP-1 agents for treatment of alcohol use disorder are underway or awaiting publication. At least one other trial is investigating use for opiate addiction.

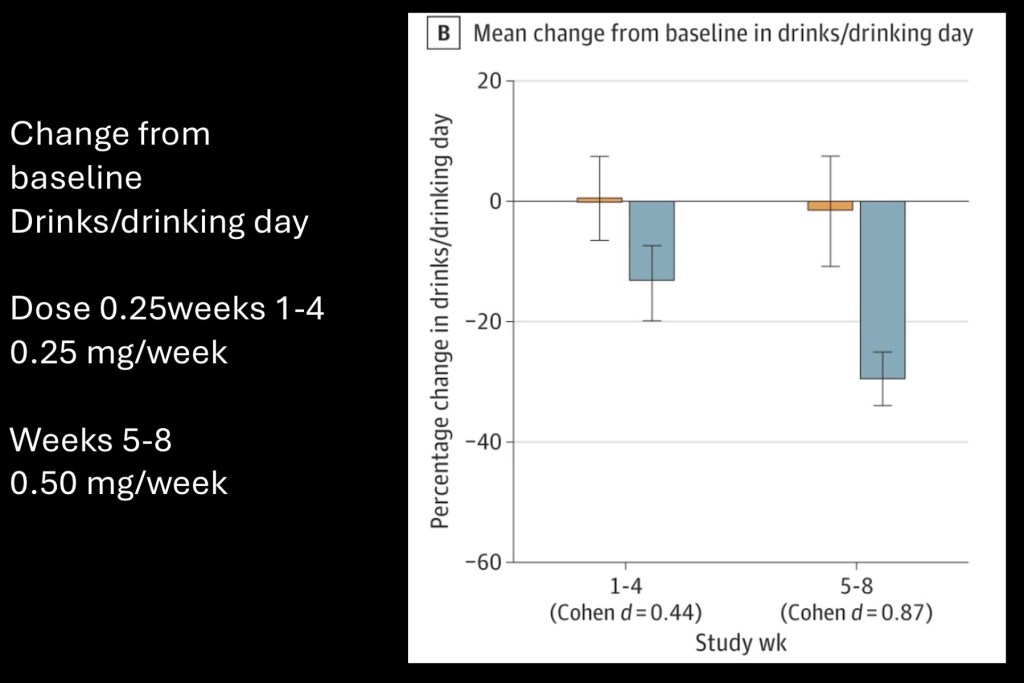

This was published recently in JAMA psychiatry. It is a small single center randomized level 2 controlled trial.

The study consisted of 48 volunteers who met criteria for active alcohol use disorder. The investigators intentionally chose subjects not actively seeking treatment for AUD in order to observe direct medication effects.

The study ran for eight weeks. During the first four weeks a 0.25mg dose of semaglutide (Ozempic) was administered. This was followed by an additional weekly 0.50mg dose. A concurrent human laboratory component was obtained and included in the same article.

Graph showing change in mean drinks/day at 0.25 and 0.50mg.

Placebo resulted in no significant change. The treatment group had dose dependent decreased consumption with approximately average 30% lower intake at 0.50mg. from baseline.

On the left percent drinking days decreased up to 22% however no significant difference was present for the treatment group compared with placebo.

The graph on the right reflects self reported subjective craving scores. Significantly decreased craving was reported by the treatment group.

Initial anecdotal reports have prompted randomized clinical trials using GLP-1 agonists in individuals meeting criteria for alcohol use disorder. This post briefly looks a the first published RCT using the medication Semaglutide in non treatment seeking individuals with AUD.

Positive effects were seen in reduction of alcohol consumed and subjective craving scores with lower doses than commonly used for weight loss. This may result in cost savings as well as decrease in unwanted effects when used for treatment of AUD. Based on these results a stronger response occurred compared with current pharmacotherapy. The study supports the need for larger multi centric trials.

…………………………………………………………………

For information and educational purposes only. This post should not me considered medical or professional advice. Images and data obtained from sources freely available on the World Wide Web.

Partial list of references used in preparation of this post

Katie Witkiewitz, Kimber Saville & Kacie Hamreus (2012) Acamprosate for

treatment of alcohol dependence: mechanisms, efficacy, and clinical utility, Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, , 45-53, DOI: 10.2147/TCRM.S23184

https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S23184

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.2147/TCRM.S23184

Safety and Efficacy of Acamprosate for the Treatment

of Alcohol Dependence

Stephanie L. Yahn1, Lucas R. Watterson1 and M. Foster Olive

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.4137/SART.S9345

…………………………………………………………

Acamprosate: A prototypic neuromodulator in the treatment of

alcohol dependence

Barbara J. Mason1 and Charles J. Heyser

CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets . 2010 March ; 9(1): 23–32.

https://www.drugs.com/medical-answers/acamprosate-naltrexone-compare-3571175/

………………………………………………………

Sobering Perspectives on the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder

Wid Yaseen, MD1; Jonathan Mong, MD, MSc1,2; Jonathan Zipursky, MD, PhD1,3,4

Author Affiliations Article Information

JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243340. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3340

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2816968

November 7, 2023

Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Melissa McPheeters, PhD, MPH1,2; Elizabeth A. O’Connor, PhD3; Sean Riley, MSc, MA1,4; et al

Sara M. Kennedy, MPH1,2; Christiane Voisin, MSLS1,4; Kaitlin Kuznacic, PharmD5; Cory P. Coffey, PharmD4; Mark D. Edlund, MD, PhD2; Georgiy Bobashev, PhD2; Daniel E. Jonas, MD, MPH1,4

Author Affiliations Article Information

JAMA. 2023;330(17):1653-1665. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.19761

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2811435

…………………………………………………“…………….

Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial

Raymond F Anton 1, Stephanie S O’Malley

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16670409/

……………………………………………………………….

Disulfiram

…………………………………………………………………

The effect of naltrexone and acamprosate on

cue-induced craving, autonomic nervous system

and neuroendocrine reactions to alcohol-related

cues in alcoholics☆

Wendy Ooteman, Maarten W.J. Koeter

doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.01

…………………………………………………………………………….

Meta-Analyses of Placebo-Controlled Trials of Acamprosate

for the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence

Impact of the Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavior Interventions Study

George Dranitsaris, MPharm, Peter Selby, MD, and Juan Carlos Negrete, MD

J Addict Med • Volume , Number , 2009

………………………………………………………………………….

The Efficacy of Acamprosate in the Maintenance of

Abstinence in Alcohol-Dependent Individuals: Results

of a Meta-Analysis

Karl Mann, Philippe Lehert, and Marsha Y. Morgan

Alcohol Clin Exp Res, Vol 28, No 1, 2004: pp 51–63

………………………………………………………….

Lanz, J.; Biniaz-Harris, N.;

Kuvaldina, M.; Jain, S.; Lewis, K.;

Fallon, B.A. Disulfiram: Mechanisms,

Applications, and Challenges.

Antibiotics 2023, 12, 524. https://

doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030524

……………………………………………………….

Meriem Gaval-Cruz and David Weinshenker

Department of Human Genetics, Emory University School of Medicine, Whitehead 301,

615 Michael St, Atlanta, GA 30322

Disulfiram for the treatment of cocaine dependence

Francesco Traccis 1, Silvia Minozzi 2, Emanuela Trogu 3, Rosangela Vacca 4, Simona Vecchi 2, Pier Paolo Pani 5, Roberta Agabio 1,✉

Editor: Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10767770/

Disulfiram Treatment of Alcoholism

CURTIS WRIGHT, M.D., M.P.H., RICHARD D. MOORE, M.D., M.H.Sc., Baltimore, Maryland

June 1990 The American Journal of Medicine Volume 88

Jk 06/25

Leave a comment