Part 1

This post is a short review of medications available to treat Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) following acute withdrawal. There are currently three FDA approved medications and several others with off-label indications to aid in reduction of craving and in relapse prevention.

These each have different mechanisms of action, potential side effects, and efficacy. Choice of a particular medication along with other supportive measures should be considered with a health care provider as part of an individual plan of approach in dealing with this complex disorder.

Recent SAMHSA data indicates that 12.5% of Americans will experience Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) in their lifetime. 3.8% meet criteria for moderate to severe AUD in the past 12 months. There are three medications approved by the FDA to treat AUD yet only 2% of patients diagnosed with this common and devastating disorder receive a prescription for medical treatment.

Medical and scientific articles detailing the results of drug trials, meta analysis, pharmacology, and diagnostic criteria concerning substance use disorders appear in major medical journals on a regular basis. Advances in neuroscience have uncovered thousands of potential targets for new drug therapies in the recent past. Three of these medications have been available for decades. Recent data indicate that $130 million has been invested into research on novel treatments for substance use disorders over the past 10 years, by comparison $36 billion was spent on cancer research in the same time period.

Particularly discouraging is the fact that of patients discharged from hospitals and emergency departments with a diagnosis of AUD fewer than one percent leave with a prescription to treat the disorder.

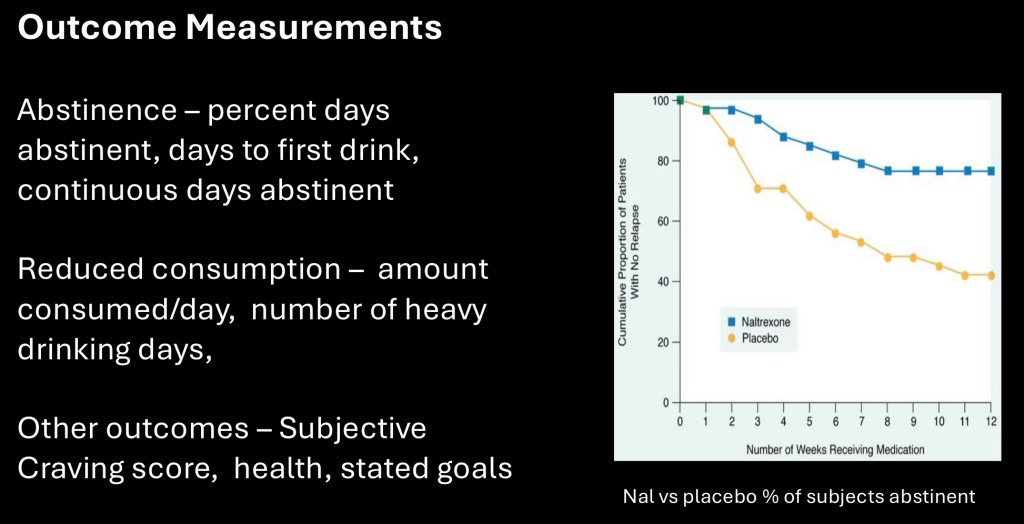

Clinical drug trials are commonly reported in the popular media. To evaluate any results it is important to note the population included and the outcome(s) measured. AUD studies are generally grouped into abstinance oriented such as %days abstinent, days to first relapse, % abstinent during the study period, or consumption oriented such as average consumption/day, number of heavy drinking days, or decrease in consumption since baseline.

Other measures may include compliance rate, subjective craving ratings, or other health outcomes.

The placebo effect tends to be strong in addiction studies. This example is taken from the COMBINE study published in 2003. The large multi center placebo controlled trial assigned subjects to combinations of either medical management (MM), Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI) and naltrexone or acamprosate. The goal was to find criteria which could be used to assign patients to treatments most likely to be successful.

The above three groups received either placebo + one of the interventions or CBI only. All of them did much better at the end of the trial with placebo + MM/CBI. In these conditions the actual benefit of a medication may be underestimated.

Acamprosate (Campral) was developed and marketed by a Merk subsidiary in Europe in 1989. It was approved by the FDA as a treatment for Alcohol Use disorder in 2004.

Acamprosate is not metabolized in the liver and can be used in individuals with hepatic dysfunction. It has low bioavailability requiring a relatively large dose. Standard dose is 2 tablets, 333mg each, three times a day. The most common side effect is diarrhea which most often resolves in the first few weeks. A lower initial dose is often used.

It is available as a generic. One month cost in the US is around $56 – $120. Acamprosate is not narcotic and has few interactions with other medications. Some patients report feelings of irritability which most often resolves in the first few weeks. It may be given prior to abstinance from alcohol. The dosing schedule makes compliance an issue in some individuals. It is not available in an extended release or injectable form.

The mechanism of action in reduction of alcohol cravings and relapse prevention is unclear. It acts as a partial NMDA glutamate antagonist and is also thought to act as an allosteric modulator of GABAa receptors. The effects appear to result in helping to balance excitatory glutamate and inhibitory GABA neurotransmitters affected by chronic alcohol use.

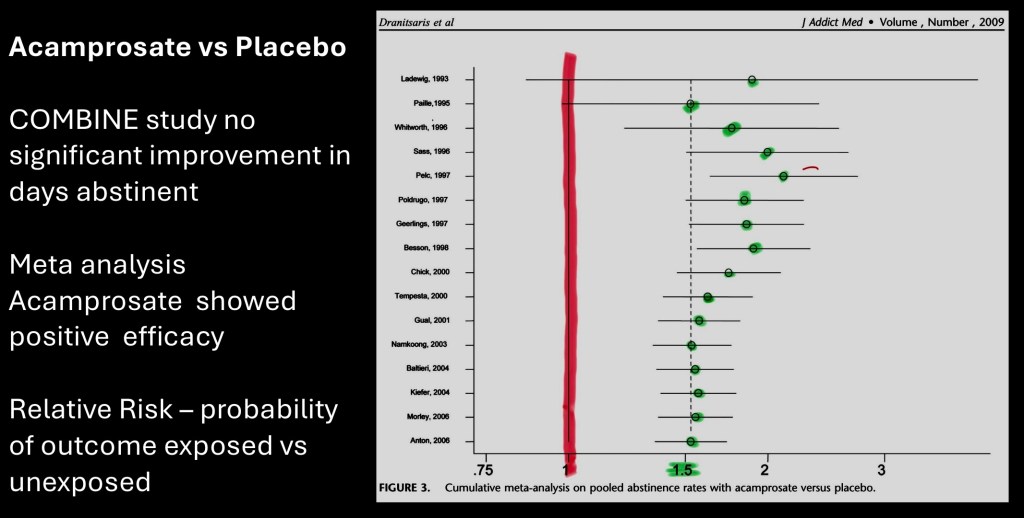

This is from a meta analysis of randomized clinical trials published in j addiction medicine in 2009. The earlier COMBINE study did not demonstrate an advantage of acamprosate over placebo. The authors hypothesized that a large placebo effect seen in that study may have masked clinical benefit identified in previous studies.

Above plot of relative risk for abstinance rates shows a consistent benefit of acamprosate over placebo utilizing pooled data. Overall patients randomized to acamprosate were 58% more likely to remain abstinent.

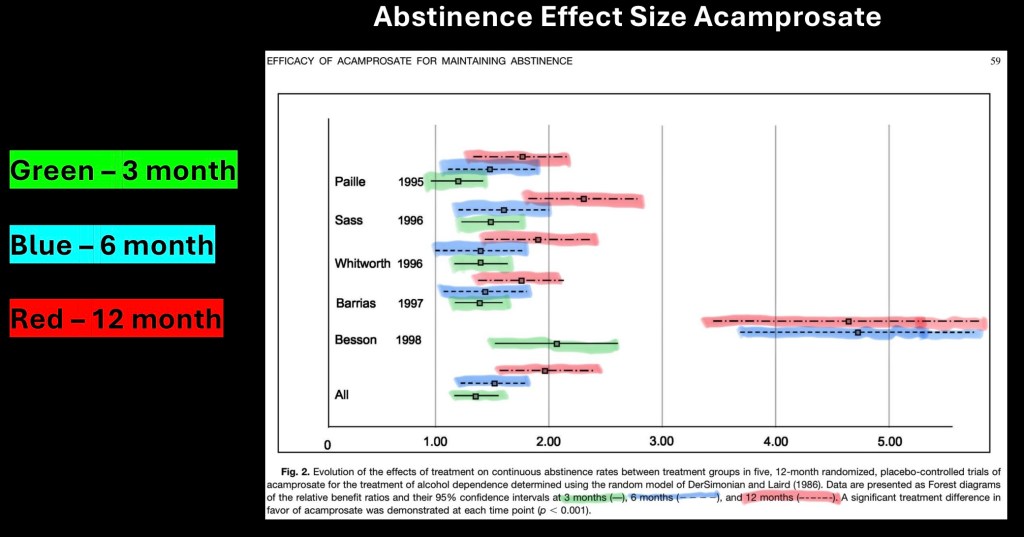

Meta analysis of abstinence rates acamprosate vs placebo at 3, 6, and 12 months treatment (color added). Horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Other than one outlier results appear consistent and reproducible in the included studies.

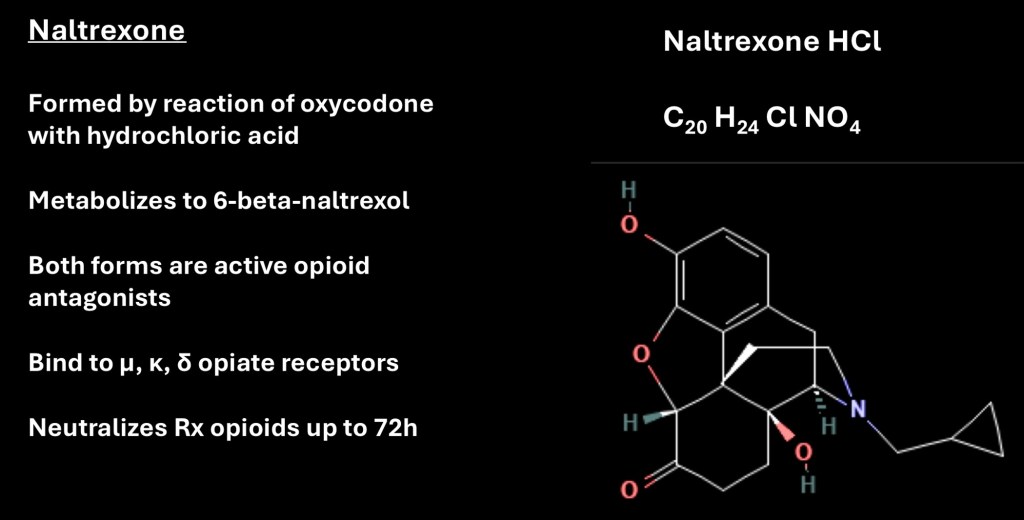

Naltrexone was first synthesized, along with the shorter acting related pharmaceutical Naloxone (Narcan) in 1963. It was studied and eventually FDA approved for treatment of opioid use disorder in 1984.

After it was introduced for treatment of OUD anecdotal evidence emerged from patients who reported less desire for alcohol and decreased hedonic effect of alcohol.

Standard oral dose is 50mg/day. Most common side effects are nausea and headache. Fatigue and sleep disturbance have been reported. Often an initial lower dose of 25 mg/day is used to minimize side effects,

A long lasting depot injection is available (vivitrol) which can be given monthly.

Naltrexone is rapidly metabolized to 6 βnaltrxol which has a longer half life than the parent compound. It is a strong opioid receptor antagonist primarily at μ receptors although it does have activity at κ and δ receptors. One consequence of treatment is prescription opioids are ineffective for up to 72 hours following oral naltrexone which may be an issue in emergency situations or patients receiving opioid medication for chronic pain.

Oral naltrexone shown here has a short biological half life. The active metabolite however has a longer half life about 8 hours. The lower graph shows pharmacokinetics of multiple daily doses superimposed on steady state plasma levels from the monthly injection. The gray bar indicates the therapeutic window. A once daily oral dose is considered sufficient to attain therapeutic levels for the 24 hours between doses.

Naltrexone levels in plasma are not directly indicative of effectiveness. Once at least 90% of receptors are occupied the drug has reached maximal effectiveness. For this reason 100mg/day or split dosing has not demonstrated significant additional benefit.

Naltrexone has two principal effects in treatment of AUD. It reduces craving for alcohol. It also tends to reduce hedonic reward and quantity consumed in people who do drink while taking the medication.

The mechanism of action is illustrated above. Alcohol induces at least some of its rewarding effects by release of endorphins. Mu-opioid receptors then block the inhibitory effects of GABA neurons in the reward pathway and a dopamine signal occurs. Naltrexone blocks this from happening reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol. It has been pointed out that this is likely only a partial explanation.

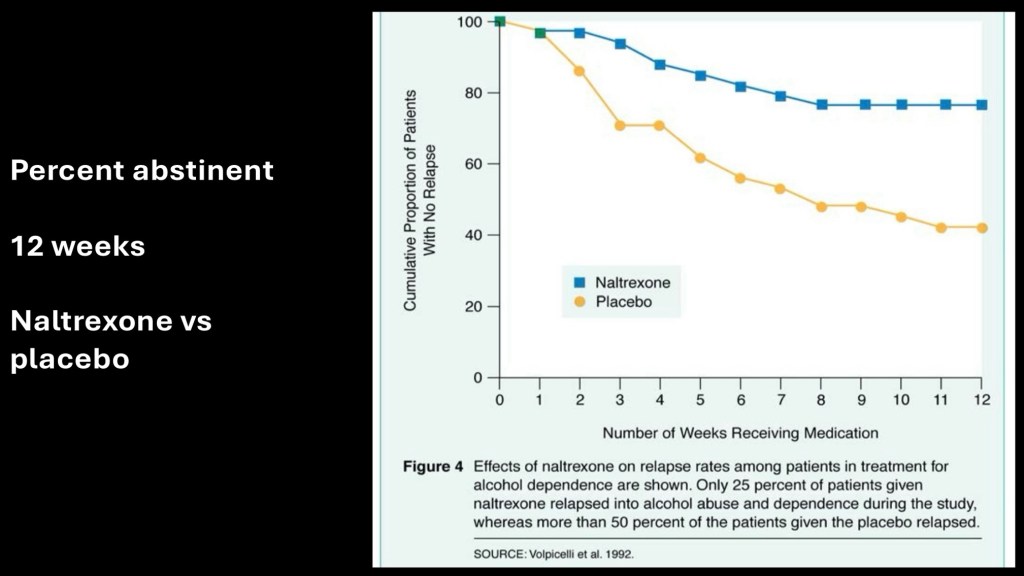

One of the earlier studies on use of naltrexone for AUD. Average subjective craving rating measured during the 12 week trial. Naltrexone subjects are shown in blue. Modest reduction is shown to the 12 week limit.

This demonstrates percent of subjects remaining abstinent during the study. All subjects were detoxed prior to the start point. By the end of the study approximately 80% of the naltrexone group and 40% of the placebo group remained abstinent.

From a meta analysis JAMA 2023. This plot reflects the relapse rate from studies using short term oral naltrexone vs placebo. Findings are expressed as an odds ratio reflecting probability. Numbers to the left of the red line favor naltrexone. To the right scores favor placebo. Horizontal bars reflect 95% confidence interval.

The overall conclusion stressed that both naltrexone and acamprosate are first line treatments for AUD. Improved results are consistently seen in individuals also receiving psychosocial treatment/support.

This study was performed in hospitalized patients with a diagnosis of AUD. The subjects were assigned to receive either oral naltrexone or vivitrol injection prior to discharge with 3 month follow up. At the follow up appointment -38.4% and – 46.4% reductions in heavy drinking (>5 drinks) days were seen in the oral and injection groups respectively. The study underscores positive benefits of initiating treatment prior to initiating a comprehensive treatment plan.

With some small differences the overall efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate are approximately equal. Some of the relative advantages of one over the other are summarized above.

………………………………………………………………………..

This is the first part of a two part post on pharmacotherapy in treatment of alcohol use disorder. References to be included in the subsequent section.

For information and educational purposes only. This post should not be considered medical or professional advice. Data and images obtained from sources freely available on the World Wide Web.

Jk/6/25

Leave a comment