‘Dopamine 2.0

Prediction, Learning, Addiction

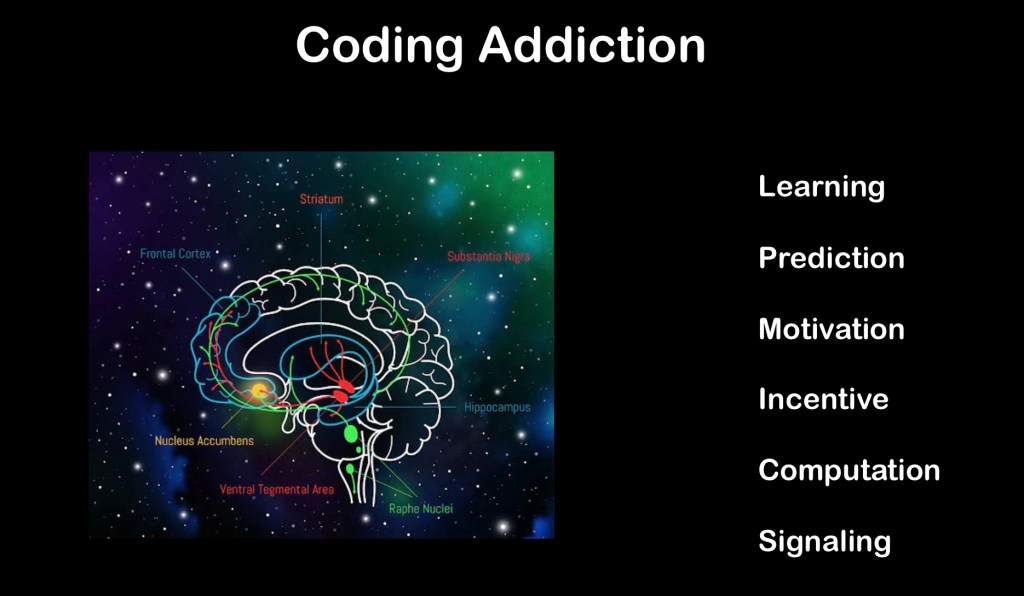

The mesolimbic, mesocortical, nigrostriatal, and tuberoinfudibular dopamine pathways play a key role in diverse pathologies including addictions, ADHD, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s disease. Dopaminergic neurons reach from the midbrain to the striatum, neocortex, motor areas, Thalamus, and extended amygdala. Beyond basic stimulus-reward, dopamine activity results in complex qualitative coding, relative values of positive and negative rewards, and economic utility. Dopamine signaling alerts us to actions and environments likely to lead to desired outcomes.

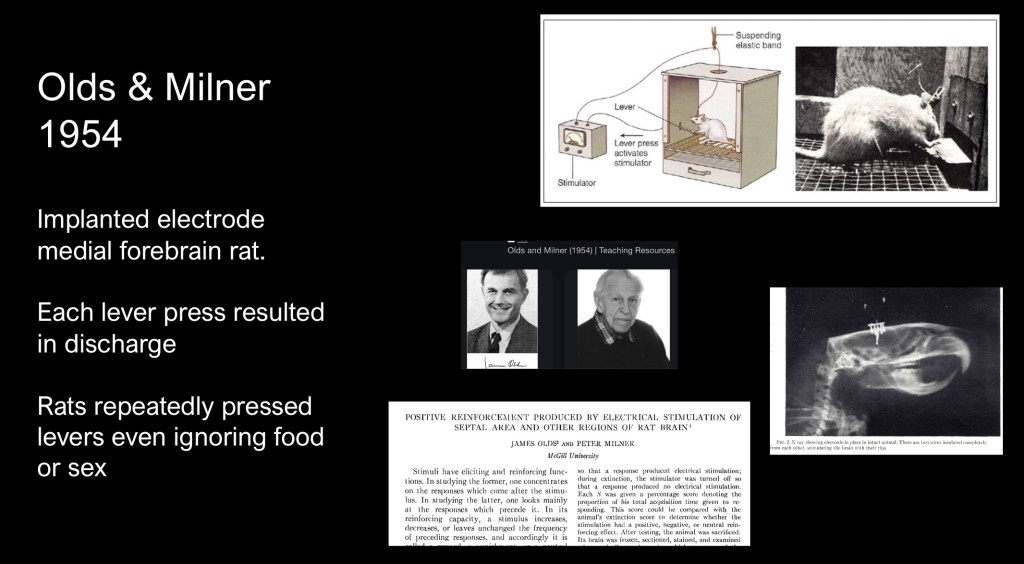

A landmark series of experiments conducted by James Olds and Peter Milner at McGill University published in 1954 opened a new era in understanding of the role played by activation of specific brain centers in behavior and reward acquisition.

The animal experiments consisted of micro electrodes implanted in the septum, nucleus Accumbens and other centers activated when the rat pressed a lever in the operant chamber. A conditioning phase was followed by extinction and then self stimulation by lever press with results recorded at different electrode locations,

It was found that in certain areas the rats would continually rapidly press the lever to the point of exhaustion even ignoring natural rewards such as food or mating. Electrode placement in other areas resulted in aversive behavior. Earlier conclusions attributing the effect to pleasure were incorrect. The effect was likely due to involuntary stimulation of a movement control center.

As summarized by the authors “there are numerous places in the lower centers of the brain where electrical stimulation is rewarding in the sense that the experimental animal stimulate itself in these places frequently and regularly for long periods of time if permitted to do so.”

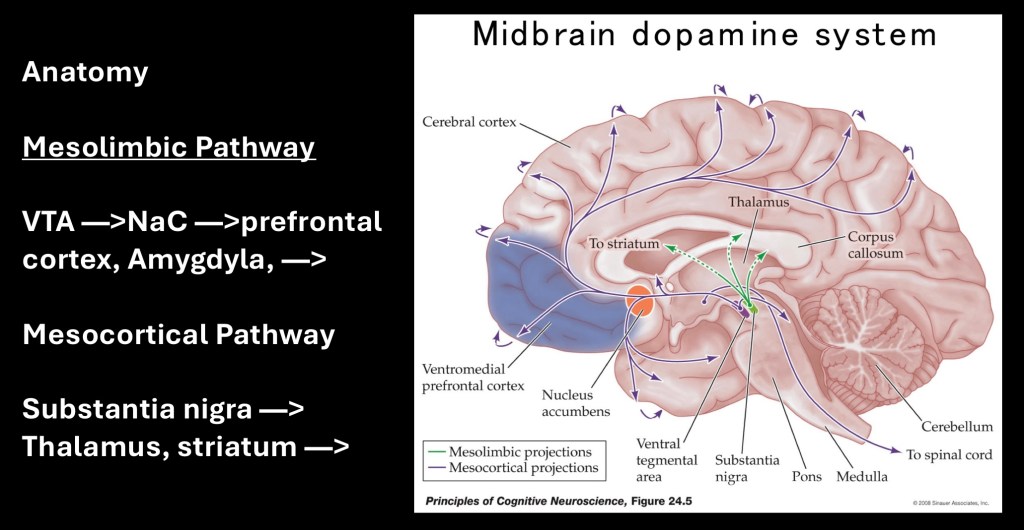

Dopamine neural bundles originating in the ventral tegmental area in the midbrain terminate in the nucleus accumbens. Additional pathways extend to the frontal and parietal cortex as well as the Amygdala. An additional bundle mostly concerned with control of motor movement arises from the substantia nigra to the striatum and thalamus.

Dopamine neural pathways are involved in reward, motivation, control of movement and cognitive processing. The dopamine pathways play central roles in diverse disease processes including schizophrenia, ADHD, addictions, Parkinson’s disease, and restless leg syndrome. This raises the question of how a single neurotransmitter which is not as abundant and widely distributed as others can have such diverse roles in seemingly unrelated pathologies.

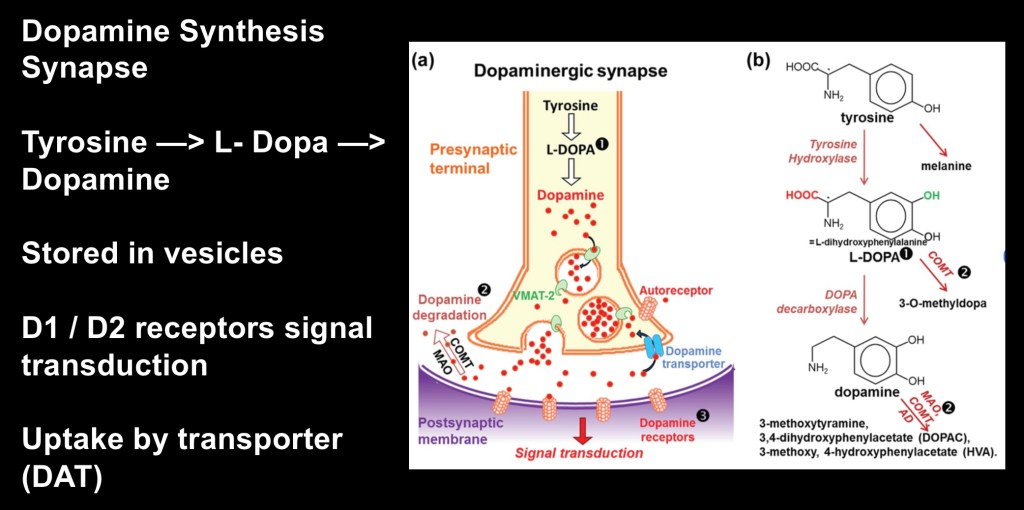

Dopamine (DA) is synthesized from the amino acid Tyrosine in a two step process shown above. It is first converted to L-Dopa by the enzyme Tyrosine Hydroxylase and then into Dopamine by the enzyme DOPA decarboxylase. It functions as both a hormone and a neurotransmitter. Dopamine does not cross the blood brain barrier. The precursor l-dopa does cross the blood-brain barrier and is used for treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

The precursor amino acid Tyrosine is abundant in the average diet. It can also be synthesized by the liver if needed. Dopamine is produced by dopaminergic neurons in response to local conditions. There is no central or peripheral pool of dopamine other than what is within neuronal vesicles. The dopamine transporter DAT removes excess dopamine from the synapse controlling extra cellular dopamine levels and duration of neural signaling.

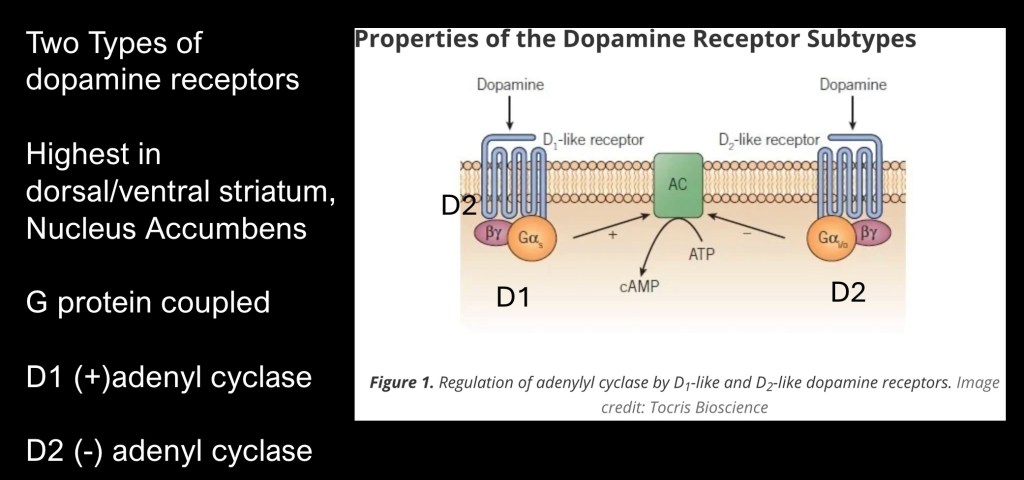

There are six known dopamine receptor subtypes. These can be functionally divided into type 1 and type 2 (D1 and D2) receptors. Both of these are G-protein coupled metabotropic receptors. They are not direct ion gates. When activated they undergo conformational changes initiating a cascade of reactions in the receiving cell. Shown here is the first reaction, D1 receptors activate the enzyme adenyl cyclase converting ATP to cyclic AMP. cAMP is an important second messenger carrying signal from the cell membrane to initiate intracellular processes. D2 receptors inhibit cAMP formation.

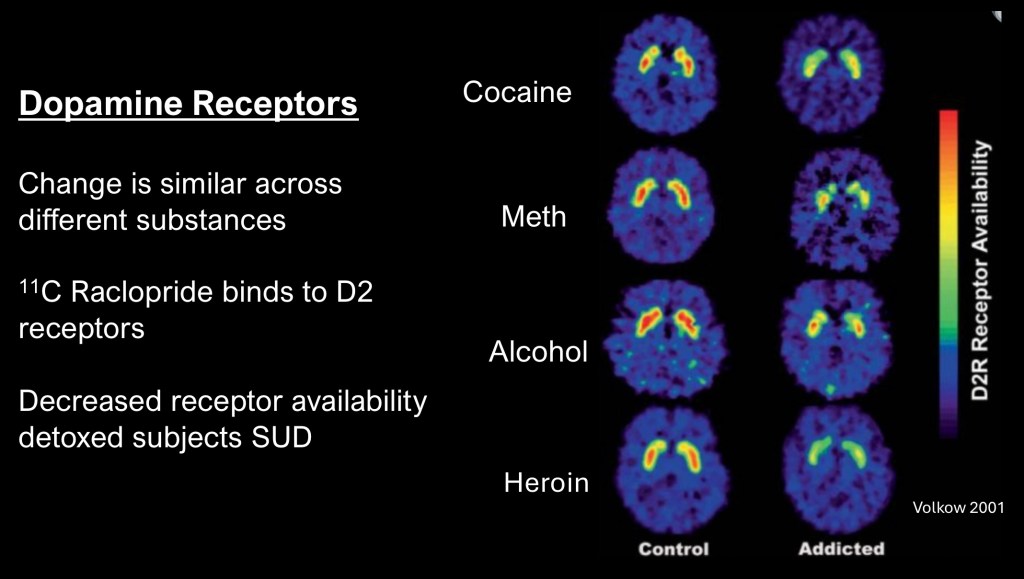

This is from a series of studies performed at the NIH and among the first using neuroimaging to demonstrate long term changes occurring in Substance Use Disorders in human subjects.

These are PET scans performed on recently detoxed individuals with history of alcohol, methamphetamine, cocaine, or heroin addiction compared with control subjects. The study used Raclopride a pharmaceutical which binds selectively to D2 dopamine receptors to which a radioactive 11C –carbon atom has been attached. The scanner can then create an image corresponding to location with the brain having greater or lesser concentration of D2 receptors.

The control images in the left column demonstrate high concentration (yellow—red) of D2 receptors normally present in an area of the brain called the striatum which forms part of the reward pathway. The test subjects show significantly lower concentration of D2 receptors, a finding which may persist for a year or more into abstinence. What is even more remarkable is the same finding despite entirely different mechanisms of these drugs.

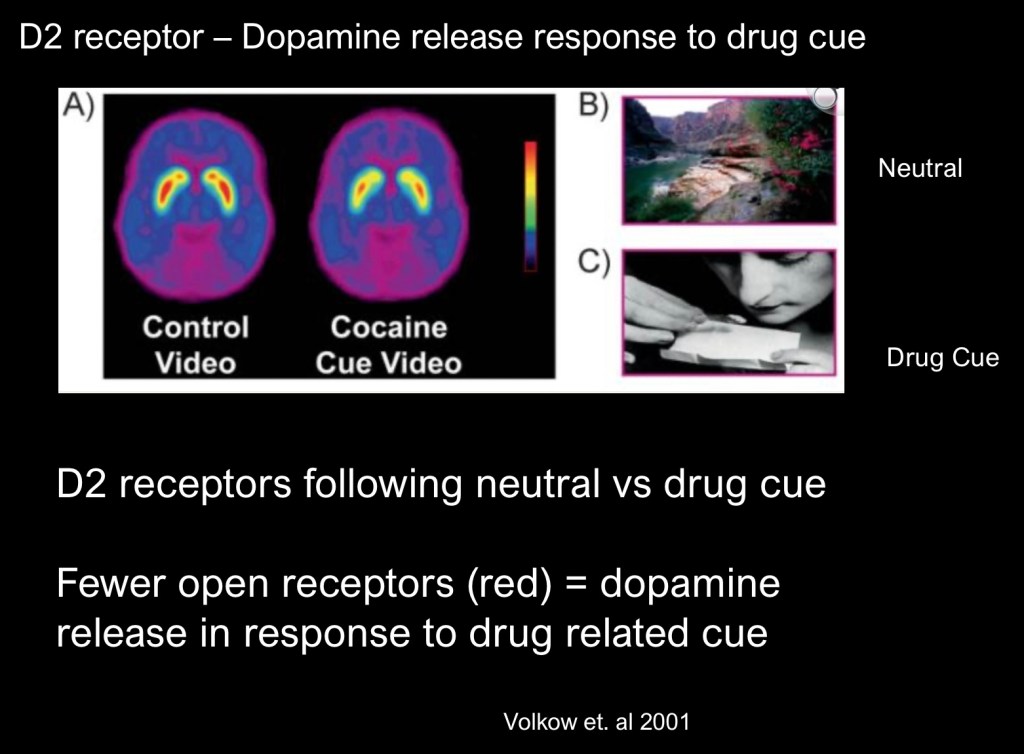

This experiment involved recently abstinent cocaine users. The study again used 11C Raclopride as the agent. The image on the left was taken from subjects viewing a neutral video cue. The image on the right represents the same subjects while viewing a drug related stimulus. Fewer open receptors are seen as less red in the center of the striatum. This indicates that dopamine release occurs not just in direct response to drug administration. Dopamine is also released in response to drug related cues in the environment.

Early studies on the reward system thought that dopamine mediated pleasure and was a simple “on-off” switch. As it turns out dopamine is much more interesting and codes for more than simple binary information.

The mesolimbic dopamine pathway fills a central role in development and progression of addictions. A central question in understanding of the reward system concerns the information in the form of neuro transmission resulting in either excitation or suppression of dopamine neurons. How do the neurons in the midbrain “know” when to fire and initiate or suppress downstream pathways.

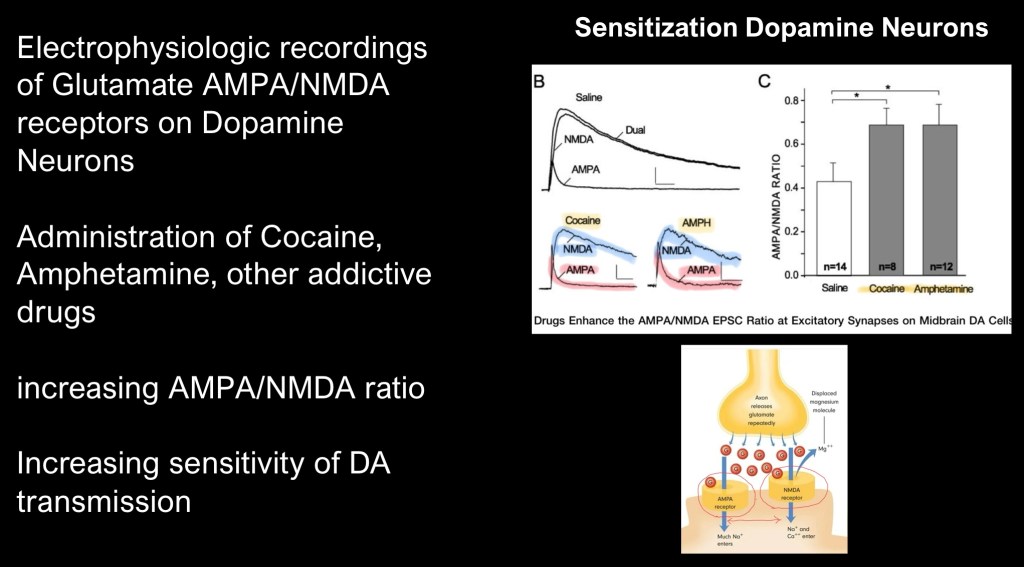

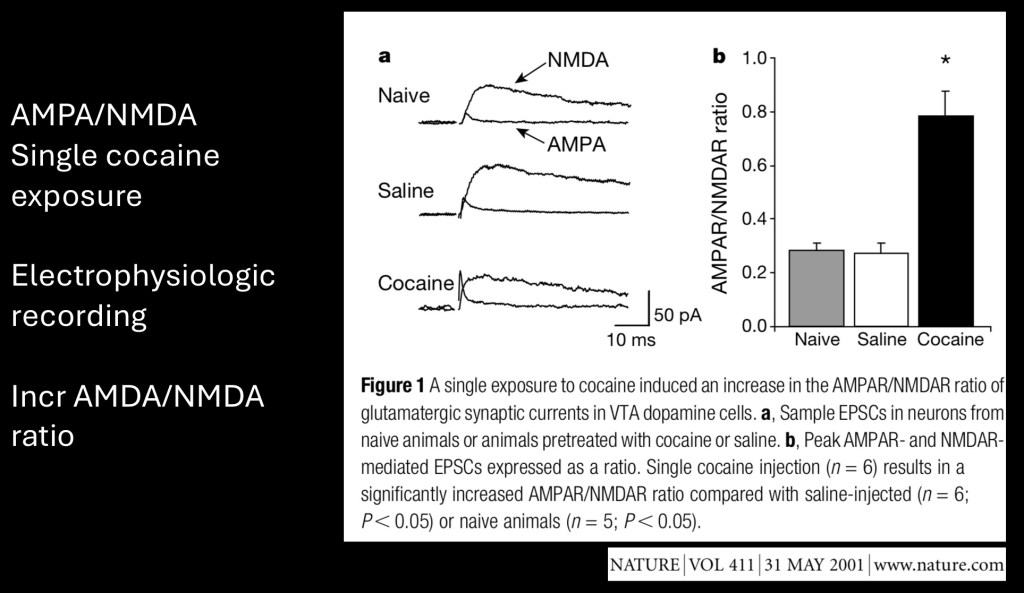

This study looked at glutamate excitatory receptors located on DA neurons in the midbrain. There are two types of glutamate receptors, AMPA and NMDA. Using electrophysioligic recording in rats the study found a shift in the ratio with increased AMPA receptors relative to NMDA receptors following repeated exposure to cocaine or amphetamines. The effect is increased sensitivity of dopamine neurons to incoming excitatory signals in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) at the origin of the reward pathway.

This expands understanding of dopamine from a simple “spike – no spike” binary signal. Addictive drugs like cocaine are capable of modifying the inputs located on dopamine neurons making them more sensitive to drug related stimuli. This differs from neutral or natural rewards,

This study looked at single cell electrophysiology and glutamate receptors on dopamine neurons. They recorded potentials in AMPA and NMDA receptors in rats following a single cocaine exposure. They found an increase in the ratio resulting from a single dose.

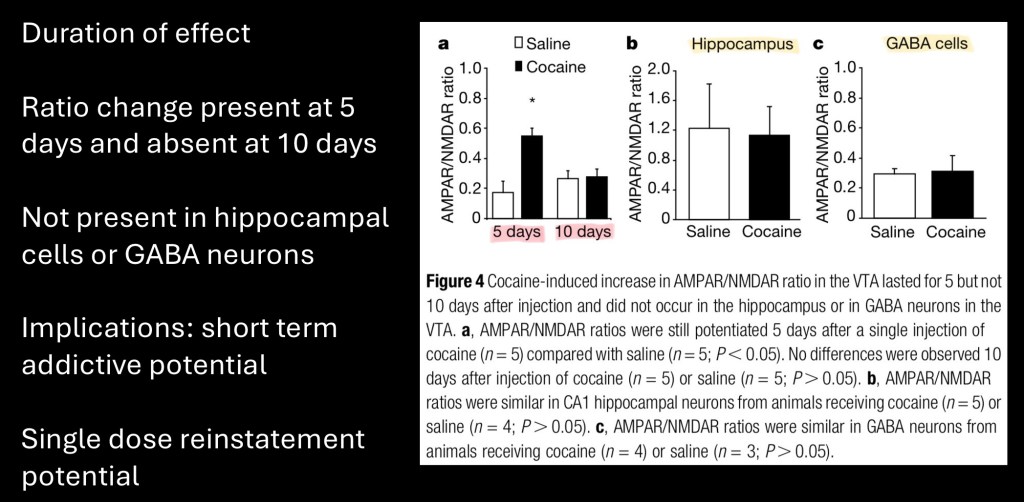

Duration of the effect in VTA dopamine neurons was measured at 5 days post exposure and at 10 days. No appreciable effect was observed at 10 days indicating a relatively transient short term sensitization. No similar changes were identified in the hippocampus, an area important in associative memory, or in GABA neurons in the VTA.

Sensitization of dopamine neurons in response to a single dose of cocaine has implications in explaining the highly addictive nature of this drug. It may also partially account for reinstatement of addictive behavior following a period of abstinence.

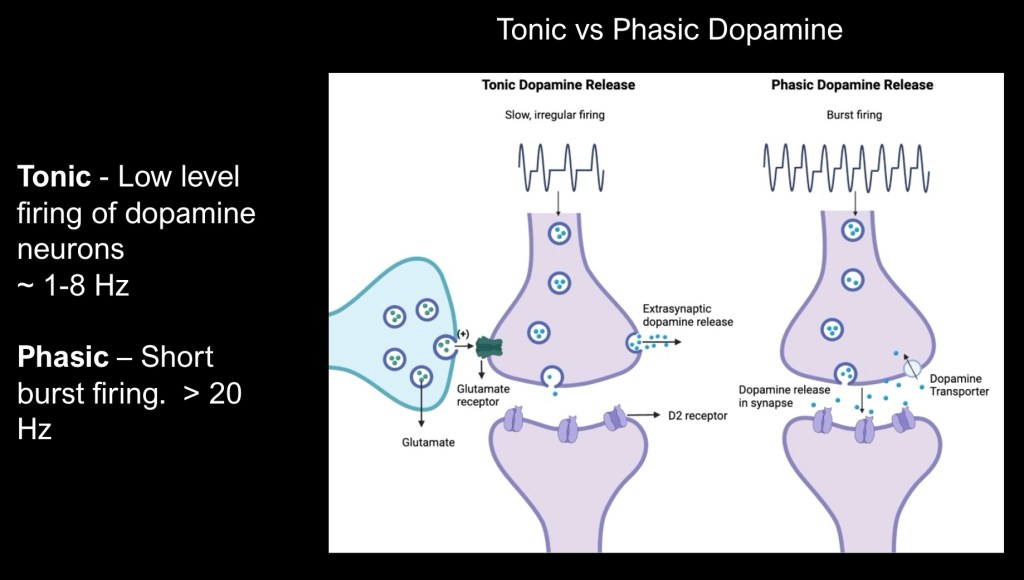

One way in which dopamine neurons convey more complex information is by variation in the duration and type of firing pattern and release into the synapse.

In some circumstances dopamine is released in a varying but steady state pattern described as tonic release. In response to other stimuli a rapid short burst of activity occurs described as phasic transmission. Duration is limited by dopamine transporter activity removing excess dopamine from the synaptic space.

Post synaptic receptor activation varies depending on both dopamine level, location and and firing pattern.

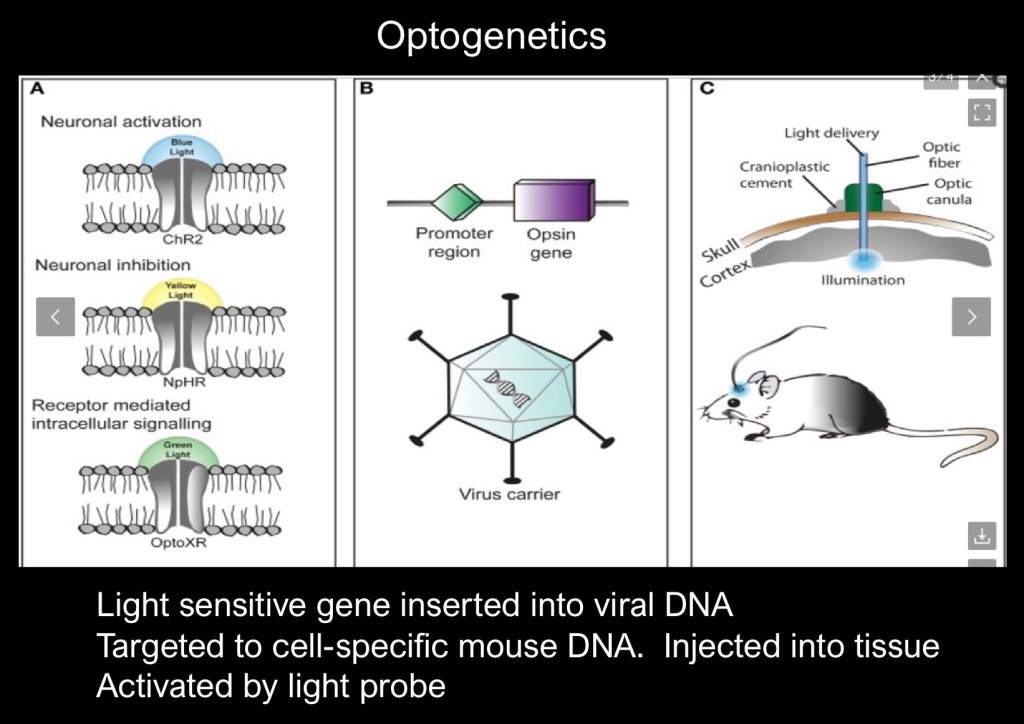

The next section describes how phasic vs tonic dopamine activity can directly influence behavior but requires some explaination of an innovative and powerful technique – optogenetic stimulation.

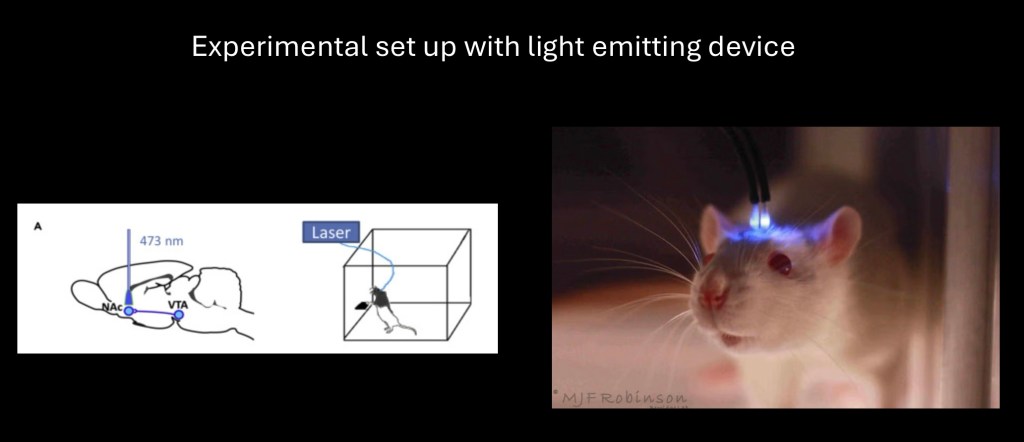

Optogenetics involves insertion of a light activated Opsin gene into the host DNA. The gene is inserted into the promoter region of the host target DNA by micro injection in the structure of interest.

Once it is in place a surgically implanted laser emitting light at the sensitive frequency will selectively activate the target gene generating the desired response.

The technique is versatile and may be used in visceral organs as well as the brain to selectively activate individual genes in live animals under experimental conditions. There are potential human and therapeutic applications.

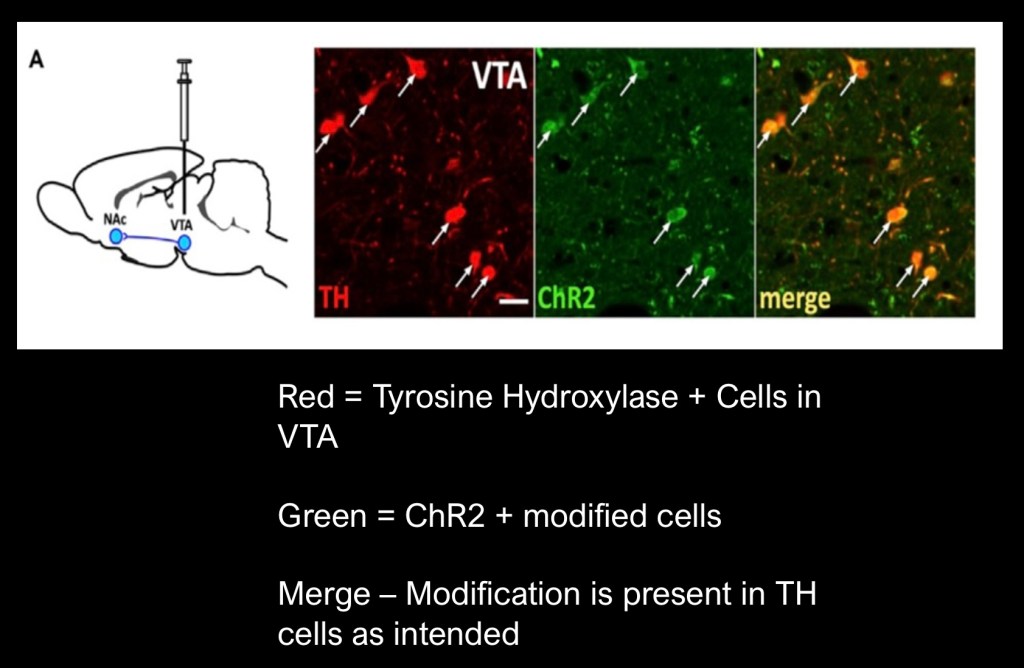

In this experiment the gene coding for tyrosine hydroxylase, the first step in conversion of the amino acid tyrosine to dopamine, was targeted and tagged with a red fluorescent marker. The green light sensitive Opsin ChR2 was inserted by micro injection into the VTA of the mice test subjects.

The above images demonstrate cells positive for both tyrosine hydroxylase (red) and ChR2 (green) as shown in the composite slide (orange).

The mice had previously been conditioned to press a lever 30 times in order to receive a 20 minute reward of 10% ethanol through a sipper tube. This was followed by an extinction phase prior to the optogenetic stimulation test.

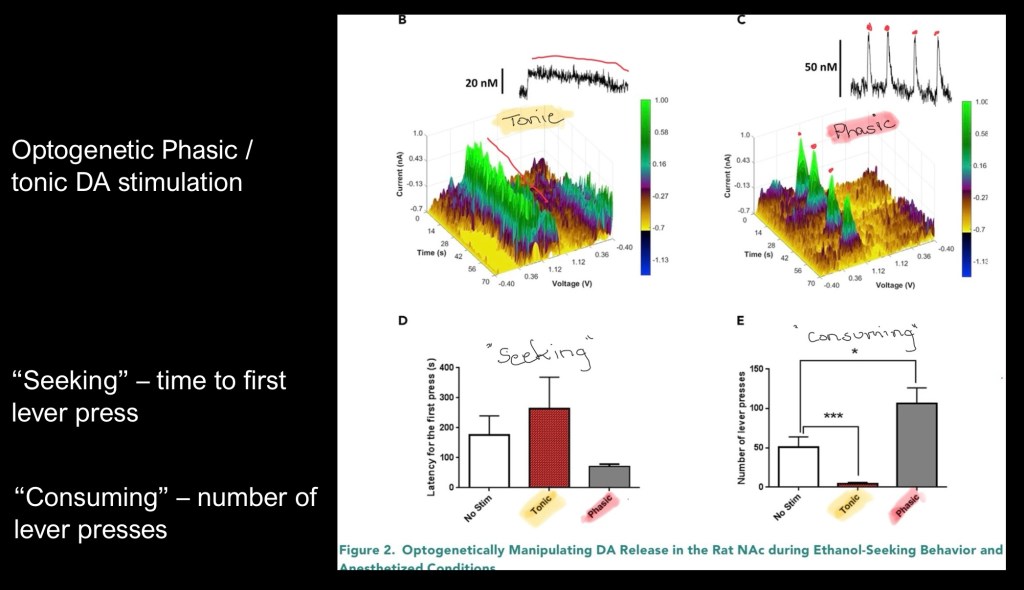

The 3D colored graphs above represent recorded electrical activity when the light stimulator was activated to generate either tonic – steady state or phasic – pulsed dopaminergic activity.

The vertical color coded axis represents amplitude. The X and Y axis represent time and voltage.

Tonic activity is shown on the left and phasic on the right.

The bar graphs represent results following tonic and phasic optogenetic stimulation.

Lower left represents latent time to first lever press or “seeking” behavior. The animals took longer to initiate a press with tonic stimulation than either of the other conditions. Phasic stimulation resulted in a faster response time.

The lower right demonstrates number of lever presses or “consuming” behavior. Tonic stimulation resulted in fewer presses than either phasic or no stimulus. Phasic stimulation resulted in significantly more lever presses.

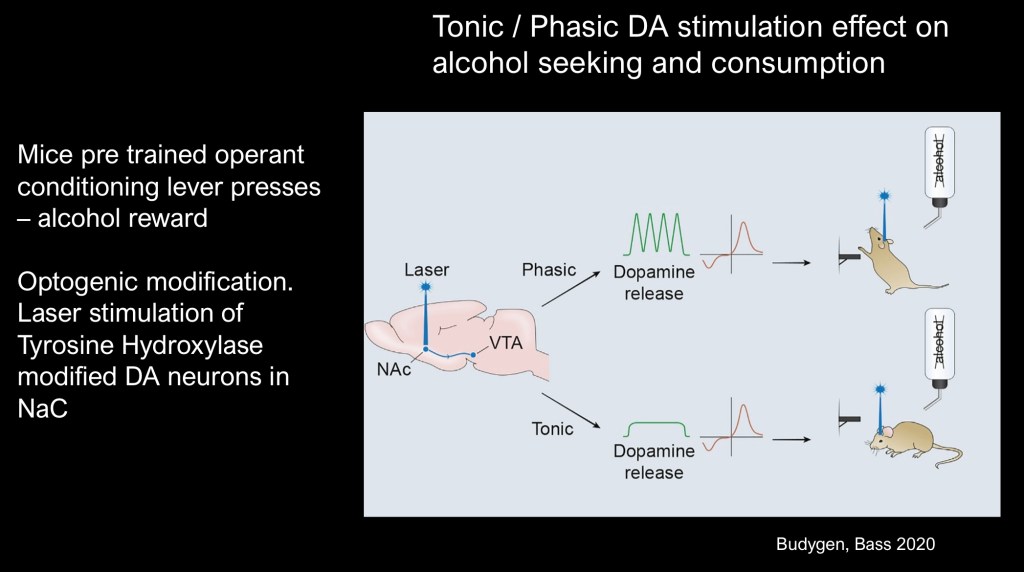

Graphic summary of this experiment.

Using optogenetic stimulation tonic dopamine release resulted in less alcohol seeking and consumptive behavior than baseline conditions. Phasic stimulation resulted in more seeking and consumptive behavior in previously conditioned mice.

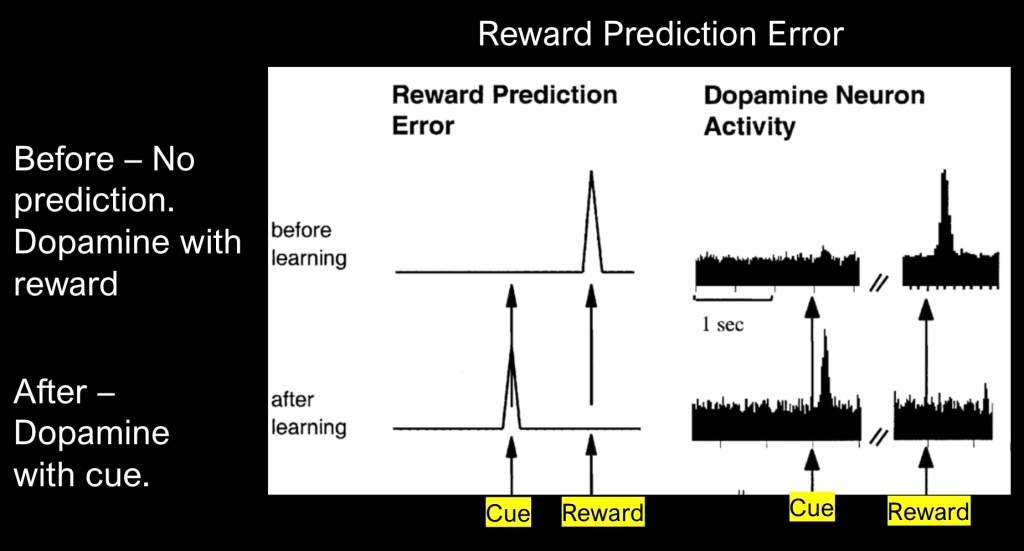

An important concept in the function of dopamine reward system is reward prediction error (RPE). The above shows basic prediction error as a graph on the left and on the right as a representative recording of corresponding dopamine activity.

The upper graph demonstrates what occurs when an unexpected reward occurs. A spike of dopamine occurs as my brain registers the unexpected reward. I open the refrigerator door and find a slice of my favorite strawberry cheesecake,

Below illustrates what occurs when a cue precedes the reward. The dopamine spike now occurs when the cue is presented and not the reward itself. A white grocery bag on the counter indicates my spouse has stopped at the bakery and always picks up more cheesecake. I have now learned something.

In classical RPE a gradual learning process occurs from the initial surprise to full cue recognition. There are additional variations by which dopamine transmits information.

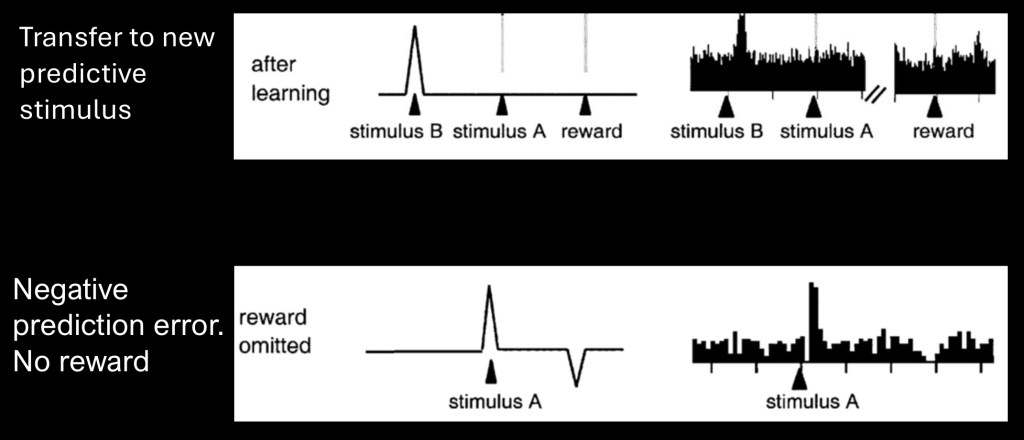

The upper graph shows transfer of the dopamine spike to a new predictive stimulus after learning has occurred. In this manner a sequence of events can become connected to a desired reward.

The lower graph demonstrates what occurs when the expected reward does not occur. In this case the prediction no longer equals the reward. Dopamine signal then drops below baseline. Thus dopamine can function in coding for both positive and negative reward predictions.

If the reward decreases or increases in value with learning the prediction will also increase or decrease to match so the prediction error will eventually equal zero.

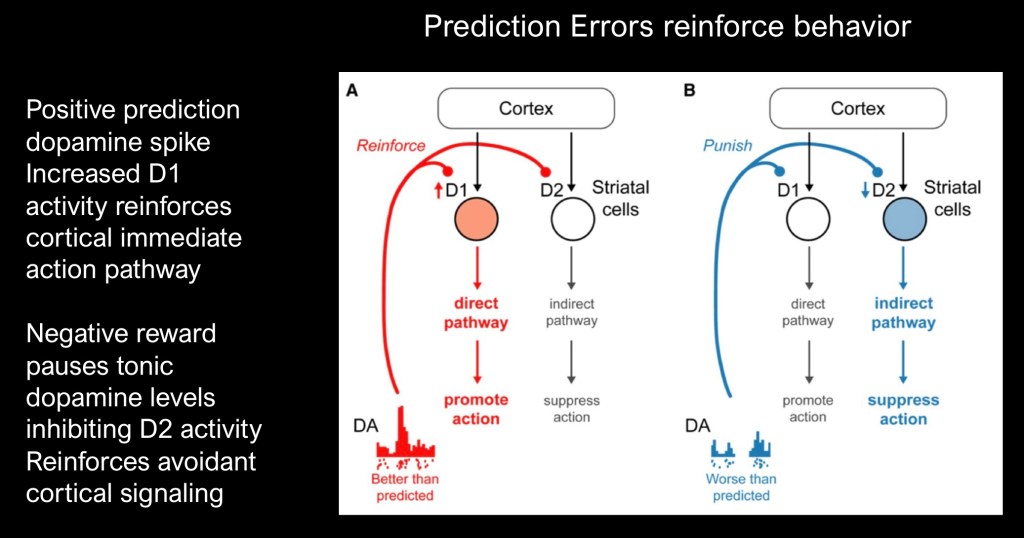

How does this signal relate to what was discussed about dopamine receptors?

When the reward is better than expected phasic increased dopamine reinforces D1 receptor activity in the striatum. This activates the cAMP mediated pathway and promotes direct action to attain reward.

When the reward is less than expected D2 tone is decreased. This results in decreased seeking behavior and reinforces avoidance.

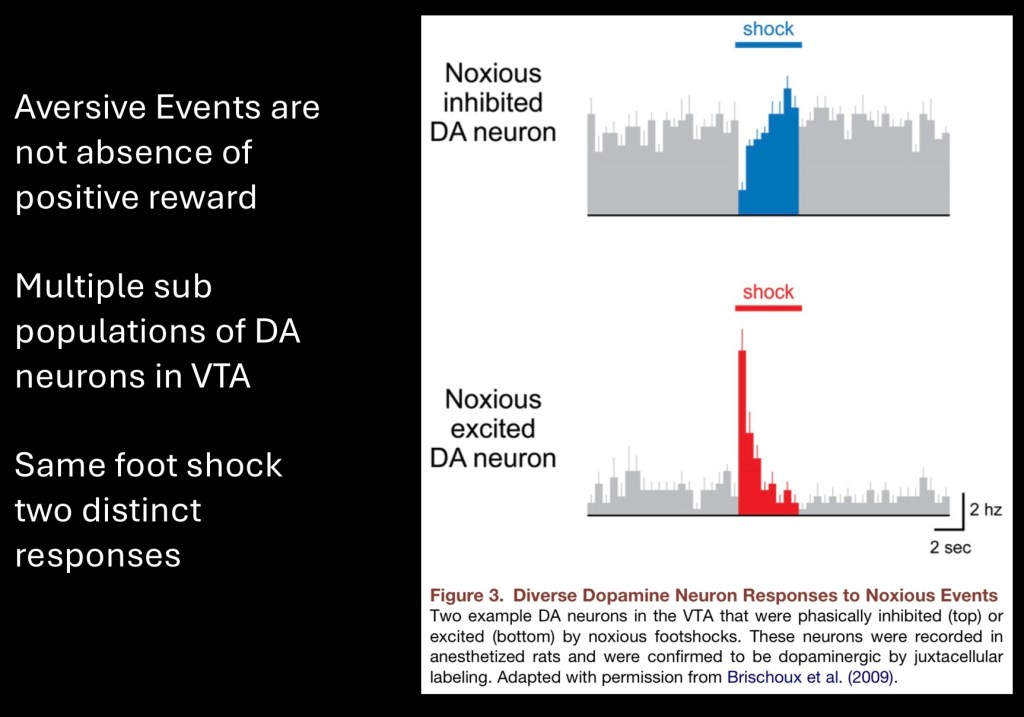

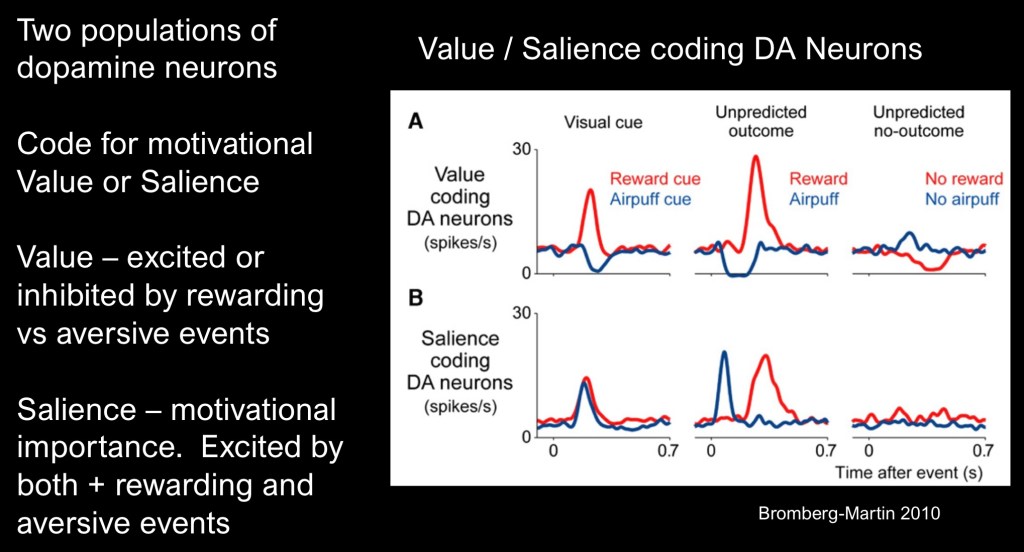

Until now we have looked at the mesolimbic dopamine pathway as a single body of neurons encoding a uniform signal. It has long been noted that the pathway encodes for both positive and negative stimuli.

There is increasing evidence that there are multiple sub populations of dopamine neurons in the VTA pathway. These represent recordings of dopamine neurons in response to foot shock. Some neurons respond with lower activity due to the aversive stimulus while others are excited.

In light of these paradoxical findings it is necessary to redefine terms. Motivation and value of a particular outcome occur in a highly complex and variable state at a given time. Finding an umbrella in the backseat of my car just as it is starting to rain is more valuable than it would have been a sunny few hours ago. Value is a state function not a constant.

We also know that dopamine can encode for discriminative properties such as more or less reward, noxious stimuli, and adjust previous motivational signal in light of new information.

These authors contend that distinct bundles of neurons signal motivational value as degrees of positive or negative valence by releasing more or less dopamine accordingly.

Motivational salience, the level of importance and attention attributed to different stimuli is encoded separately with positive and negative stimuli encoded in the same direction.

The upper row superimposes positive reward shown in blue and aversive stimuli (air puff) shown in red extending below baseline levels.

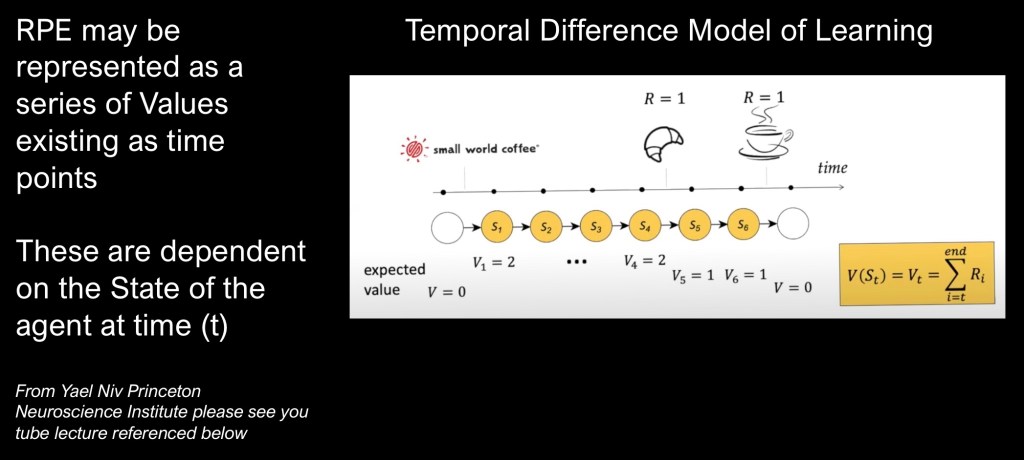

Most things encountered in life do not occur as sharp sudden events but rather as a series of occurrences over time with updated predictions and state dependent reward value. These can be combined into the Temporal Difference Model of Learning.

This example presented in the video linked to below by Yael Niv of Princeton university shows how this works in an example of her getting her morning coffee after arriving at work.

When placing her order for a croissant and coffee each has a value of 1 so RPE= 2. Over the next few time intervals nothing changes until she is handed the pastry and 2-1=RPE of 1. Then after a few more minutes she is handed the coffee and RPE equals zero. In this exchange no new information is learned.

There are many possible variations as updates and relative values may change over time but this is a useful starting point to build a model on. The subsequent section on computational models further discusses these concepts.

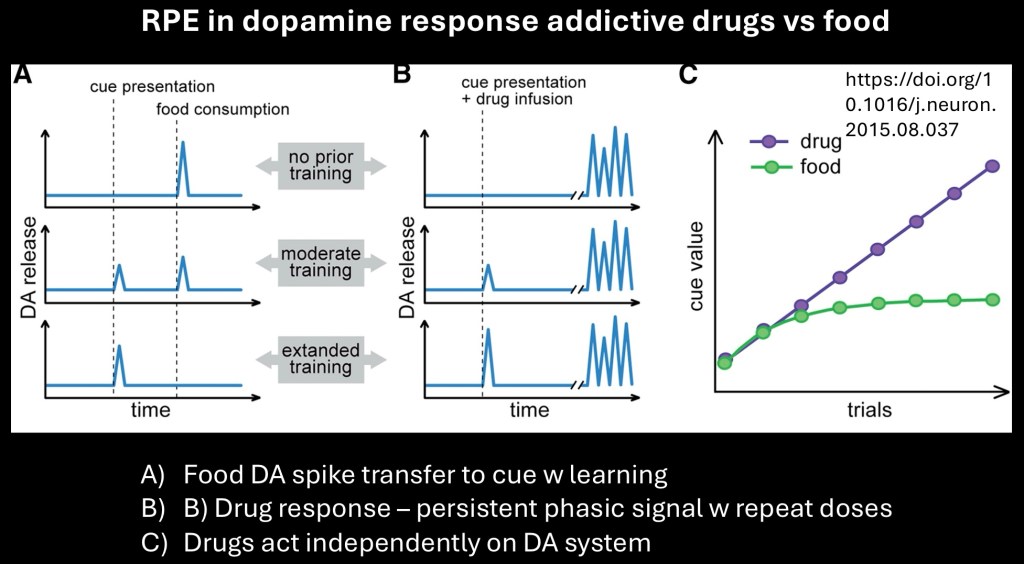

RPEs and drug reward

Addictive drugs are thought to result in maladaptive dopaminergic and learning systems. This example illustrates a putative mechanism explaining how this would operate.

The A column represent a typical RPE learning mechanism present with food as the reward. The unexpected reward appears as a DA signal. This signal is transferred to a predictive cue as learning continues. At the final stage the DA signal only occurs when the cue is presented not with food delivery.

The B column illustrates what occurs with addictive drugs. A phasic burst of activity accompanies initial drug use. With learning a DA signal is present with predictive cue. Unlike food and other natural rewards phasic DA bursts continue with each drug use. This is because addictive drugs act independently, bypassing normal controls to activate dopamine neurons.

The graph illustrates how the cue value of drugs increases over time rather than reaching a plateau occuring with natural rewards.

The next section is an introductory view of computational neurobiology as it applies to prediction errors.

Computational models of learning of learning can be developed for Reward Prediction, Temporal Difference, and other types of learning. These models can be used to test predictive value of empirically derived hypothesis and to clarify the role of various factors contributing to observed behavior.

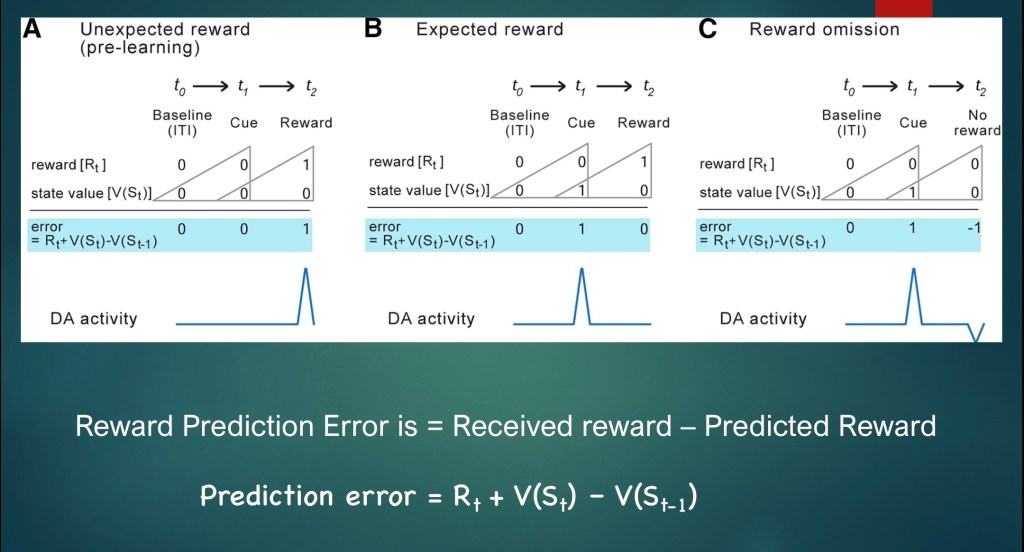

In simple terms a reward prediction error is the difference between a received reward and the predicted reward. In notation:

Rt is the Reward at time t

V(St) is state value at time t

V(St-1) is state value just preceding time t

The diagram above represents the numerical value for Rt and V(St) in each of the three labeled conditions.

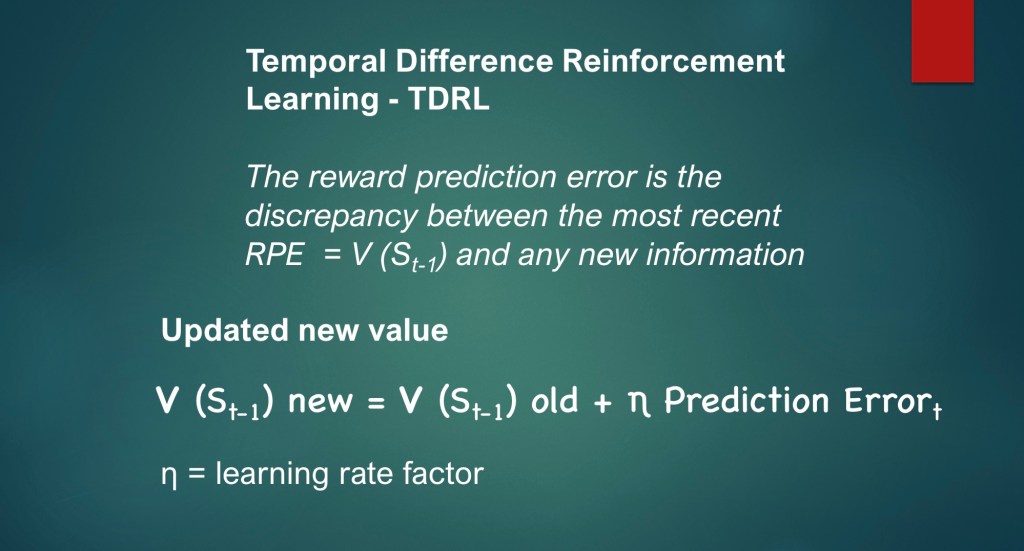

A key component of TDRL is that new information is used to update the previous prediction value.

In descriptive terms the new state value = the old state value plus the current prediction error.

η is a learning rate factor reflecting degree of complete or partial learning.

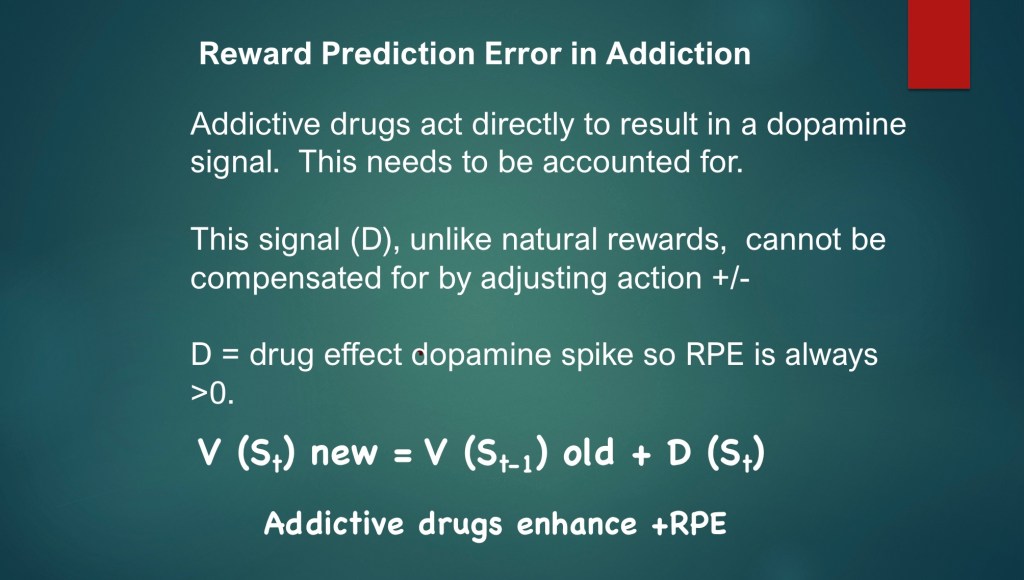

Dysfunction in dopamine reward and learning pathways are at the core of addiction. A key characteristic of addictive substances is they are capable of bypassing normal discriminative neural pathways and modulate dopamine release either directly or indirectly by a number of mechanisms including blocking of dopamine reuptake, stimulation of dopamine release, and modulation of excitatory and inhibitory control of DA neurons.

This can be represented as an additional drug effect (D) added to the state value calculation. Because the value of D is always greater than zero there is always a positive net RPE.

This model can account for known gradual loss of positive reward in addiction [V(St)] and corresponding increase in compulsive use (D)

………………………………………………………………………………….

Traditional thinking views the dopamine reward signal as a binary on/off switch responding to rewarding effects of addictive substances along with natural rewards. As newer evidence has come to light dopamine signaling in now known to influence activation or inhibition of cellular pathways governing drug seeking behavior through changes in tonic/phasic firing, synaptic dopamine levels, and selective D1/D2 receptor activation.

Temporal difference learning makes possible updated predictions concerning environment and actions likely to produce desired outcomes. Signal strength conveys bidirectional information concerning the magnitude of current and future outcomes.

Potentially addictive substances result in dysfunctional alterations at multiple levels of this system with distortions in value estimation and motivational salience. These become encoded and cumulative over time.

……………………………………………………………………….

For educational and information purposes. This post should not be considered medical or professional advice. No commercial or institutional interest. Images and data obtained from sources freely available on the world wide web

Comments and suggestions are always welcome

References

List of sources used in preparation of this post

Dopamine redux

Dopamine Prediction Errors in Reward Learning and Addiction: From Theory to Neural Circuitry

Ronald Keiflin Patricia H. Janak

Neuron Volume 88, Issue 2, 21 October 2015, Pages 247-263

……………………………………………………..,…

Parsing reward

Kent C. Berridge and Terry E. Robinson

Department of Psychology (Biopsychology Program), University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1109 USA

TRENDS in Neurosciences Vol.26 No.9 September 2003

Addiction as a computational process gone awry

A. David Redish

Department of Neuroscience University of Minnesota

Science accepted 19 October 2004

Dopamine in Motivational Control:

Rewarding, Aversive, and Alerting

Ethan S. Bromberg-Martin,Masayuki Matsumoto,and Okihide Hikosaka

Neuron 68, December 9, 2010

…………………………………………………….

Phasic Firing in Dopaminergic Neurons Is Sufficient for

Behavioral Conditioning

Hsing-Chen Tsai, Feng Zhang, Antoine Adamantidis

Science . 2009 May 22; 324(5930): 1080–1084. doi:10.1126/science.1168878.

Infographic: The Cre-lox System Explained

The Cre-lox recombination method orchestrates remarkable genetic manipulations that remain a gold standard for transgenic mice.

Infographic: The Cre-lox System Explained | The Scientist

In Vivo Whole-Cell Patch-Clamp Methods: Recent Technical Progress and Future Perspectives

by Asako Noguchi 1, Yuji Ikegaya 1,2,3 and Nobuyoshi Matsumoto 1,*

In Vivo Whole-Cell Patch-Clamp Methods: Recent Technical Progress and Future Perspectives

Habenula: Anatomy, function and clinical significance | Kenhub

………………………………………………………………………

Schultz W. Dopamine reward prediction error coding. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016 Mar;18(1):23-32. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/wschultz. PMID: 27069377; PMCID: PMC4826767.

Dopamine reward prediction error coding – PMC

Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC. The functional neuroanatomy of pleasure andhappiness. Discov Med. 2010 Jun;9(49):579-87. PMID: 20587348; PMCID: PMC3008353.

The Functional Neuroanatomy of Pleasure and Happiness – PMC

……………………………………………………

Responses of Monkey Dopamine Neurons to Reward and

Conditioned Stimuli during Successive Steps of Learning a Delayed

Response Task

Wolfram Schultz, Paul Apicella,” and Tomas Ljungbergb

lnstitut de Physiologie, Universitb de Fribourg, CH-1700 Fribourg, Switzerland

……………………………………………………………….

Mesolimbic dopamine release conveys causal associations

HUIJEONG JEONG HTTPS://ORCID.ORG/0000-0003-1219-4191, ANNIE TAYLOR HTTPS://ORCID.ORG/0000-0002-2496-9815, JOSEPH R FLOEDER HTTPS://ORCID.ORG/0000-0002-6800-7730, MARTIN LOHMANN,

SCIENCE 8 Dec 2022 Vol 378, Issue 6626 DOI: 10.1126/science.abq6740

Mesolimbic dopamine release conveys causal associations | Science

Systems Neuroscience: Shaping the Reward Prediction Error Signal

Wvviilliam R. Stauffer wrs@pitt.edu

DISPATCHVolume 25, Issue 22PR1081-R1084November 16, 2015

Systems Neuroscience: Shaping the Reward Prediction Error Signal: Current Biology

Dreyer JK, Herrik KF, Berg RW, Hounsgaard JD. Influence of phasic and tonic dopamine release on receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2010 Oct 20;30(42):14273-83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1894-10.2010. PMID: 20962248; PMCID: PMC6634758.

Influence of Phasic and Tonic Dopamine Release on Receptor Activation – PMC

…………………………………………………………………………………..

Visualizing Hypothalamic Network Dynamics for

Appetitive and Consummatory Behaviors

Jennings et al., 2015, Cell 160, 516–527

January 29, 2015 ª2015 Elsevier Inc.

………………………………………………………………………l

Drugs of Abuse and Stress Trigg

a Common Synaptic Adaptation

in Dopamine Neurons Report

Daniel Saal, Yan Dong,

Neuron, Vol. 37, 577–582, February 20, 2003,

…………………………………………………………………

Single cocaine exposure in vivo

induces long-term potentiation

in dopamine neurons

Mark A. Ungless*, Jennifer L. Whistler*, Robert C. Malenka²

& Antonello Bonci*

* Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, Department of Neurology,

NATURE | VOL 411 | 31 MAY 2001 | http://www.nature.com

…………………………………………………………………………

K

Nora D. Volkow, Gene-Jack Wang, Frank Telang, Joanna S. Fowler, Jean Logan, Anna-Rose Childress,

The Journal of Neuroscience, June 14, 2006• 26(24):6583– 6588 • 658

…………………………………………………………………………….

T.E. Robinson, K.C. Berridge

Incentive-sensitization and addiction

Addiction, 96 (2001), pp. 103-114

…………………………………………………………………………

Dopamine: The Neuromodulator of Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity, Reward and Movement Control

by Luisa Speranza 1, Umberto di Porzio 2,*, Davide Viggiano

, Antonio de Donato

Cells 2021, 10(4), 735; https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10040735

Dopamine: The Neuromodulator of Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity, Reward

……………………………………………………………….

…………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………..

Robert Heath

………………………………………………………………..

Pleasures of the brain

Kent C. Berridge*

Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1109, USA Accepted 26 September 2002

Brain and Cognition 52 (2003) 106–128

OPOSITIVE REINFORCEMENT PRODUCED BY ELECTRICAL STIMULATION OF

SEPTAL AREA AND OTHER REGIONS OF RAT BRAIN’

JAMRS OLDS AND PETER MILNK

McGUl University

…………………………………………………………….

…………………………………………………………………..

Temporal Difference Learning: Benefits & Limitations

………………………………………………………..

Dopamine: Functions, Signaling, and Association with Neurological Diseases

January 2019Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology

(PDF) Dopamine: Functions, Signaling, and Association with Neurological Diseases

………………………………………………………………..

Impaired Neural Response to Negative Prediction Errors in Cocaine Addiction

Muhammad A. Parvaz, Anna B. Konova, Greg H. Proudfit, Jonathan P. Dunning, Pias Malaker, Scott J. Moeller, Tom Maloney, Nelly Alia-Kleinand Rita Z. Goldstein

Journal of Neuroscience 4 February 2015, 35 (5) 1872-1879; https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2777-14.2015

……………………………………………………………………………………………

Soyoung Q. Park, Thorsten Kahnt, Anne Beck, Michael X Cohen, Raymond J. Dolan, Jana Wrase and Andreas Heinz

Journal of Neuroscience 2 June 2010, 30 (22) 7749-7753; https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-09.2010

…………………………………………………………..

Delay discounting, impulsiveness, and addiction severity in

opioid-dependent patients

Elias Robles, PhD,

J Subst Abuse Treat . 2011 December ; 41(4): 354–362. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2011.05.003.

Patch clamp recordings

……………………………………………………..

…………………………………………………..

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Telang F, Baler R. Addiction: decreased reward sensitivity and increased expectation sensitivity conspire to overwhelm the brain’s control circuit. Bioessays. 2010 Sep;32(9):748-55. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000042. PMID: 20730946; PMCID: PMC2948245.

………………………………………………………

………………………………………………….

IScience ARTICLEVolume 23, Issue 3100877March 27, 2020

Opposite Consequences of Tonic and Phasic Increases in Accumbal Dopamine on Alcohol-Seeking Behavior

Evgeny A. Budygin1,5 ebudygin@wakehealth.edu ∙ Caroline E. Bass

……………………………………………………………

Reduced Neural Tracking of Prediction Error in

Substance-Dependent Individuals

Jody Tanabe, M.D. Jeremy Reynolds, Ph.D.

Am J Psychiatry 2013; 170:1356–1363)

……………………………………………………….k

………………………………………………………

Dazzled by the dominions of dopamine: clinical roles of D3, D2, and D1 receptors

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 July 2017

.

Jk 05/25

Leave a comment