Cocaine

This post is a brief overview of cocaine. Use of this drug has been increasing over the past decade. It is considered to be highly addictive. Risk of developing dependence in users reporting first time use within the past 24 months is estimated at 3-5%. Cocaine is a stimulant acting by a unique mechanism distinct from amphetamines. Research efforts are focusing in on specific neuro adaptive cellular changes resulting in the addictive cycle and factors contributing to relapse risk.

The stimulant properties of the coca bush have been known to the inhabitants of central and South America for thousands of years. The harvested leaves are chewed with a low dose of the active component absorbed through the oral mucosa.

Distribution and sale of refined cocaine is a highly profitable global enterprise. The product is shipped from South America by land, sea and air to the US, Europe, Southeast Asia and other destinations. The United States is the largest consumer representing 35% of sales.

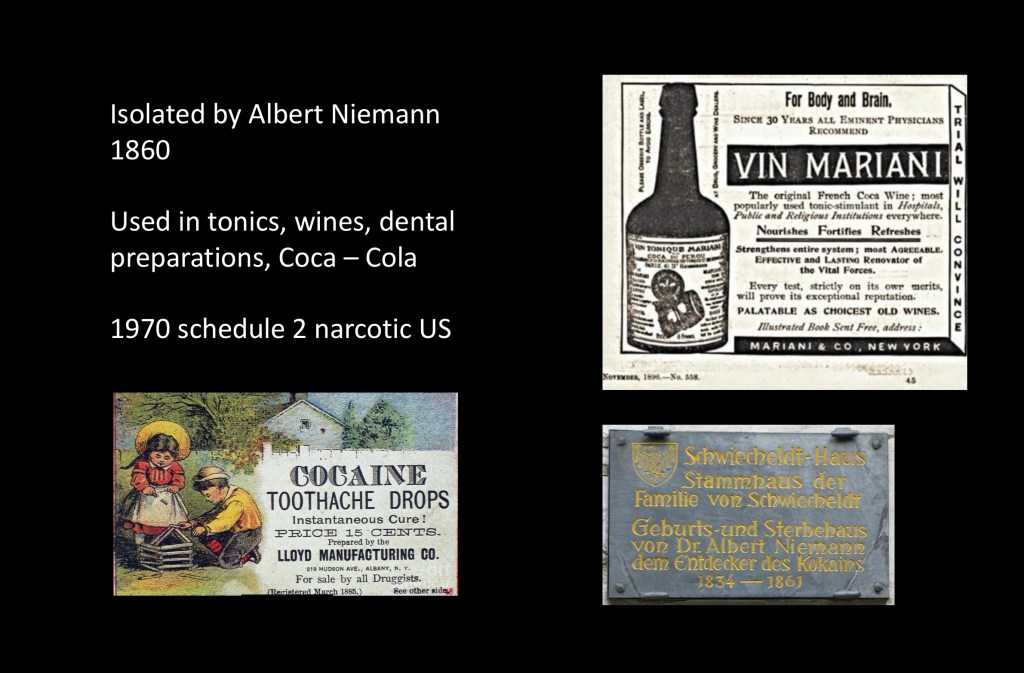

In the late 1800s Europeans took an interest in various medicinal plants used by indigenous people in the americas. A shipment of coca leaves was sent to Albert Niemann a German chemist working on his doctoral thesis for further analysis. Niemann isolated cocaine, the active component and published his results and extraction method in 1860. Niemann later became a co-inventor of mustard gas. He was to die of respiratory complications several years later.

Cocaine was soon popularized and considered a largely benign substance. It was incorporated into dental preparations as a pain reliever. Cocaine was included into fortified wines, tonics, various pharmaceuticals, and the original version of coca-cola. It later came to be seen as a more dangerous narcotic. In 1970 the FDA classified it as a level 2 drug, meaning medically restricted and potentially abused. It has been decriminalized in Portugal, several South American countries and the state of Oregon.

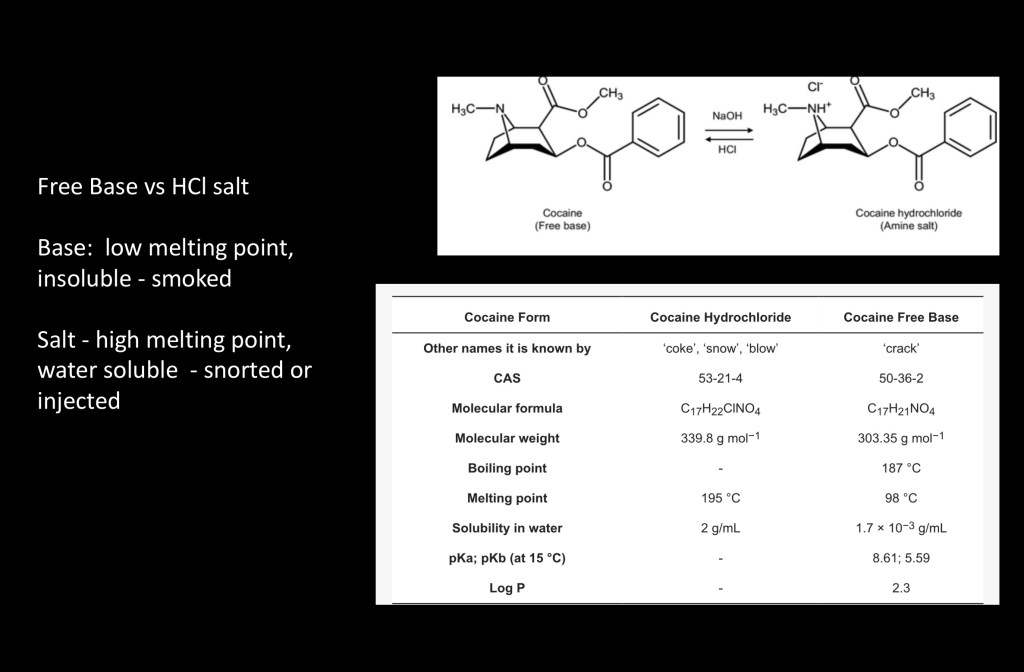

Cocaine may be present in one of two forms. The salt, cocaine hydrochloride is highly water soluble. It has a high melting point and cannot be smoked as the high temperature needed destroys the compound. In this form it is either taken by nasal insufflation (snorted) or intravenous injection. Oral use is inefficient.

The hydrochloride can be converted to the freebase form (crack cocaine) by addition of baking soda or lye. It has a low melting point and can easily be vaporized and smoked. The large surface area of the lungs allows rapid absorption into the bloodstream. It is highly insoluble in this form. By weight crack cocaine is not actually more potent than the hydrochloride form.

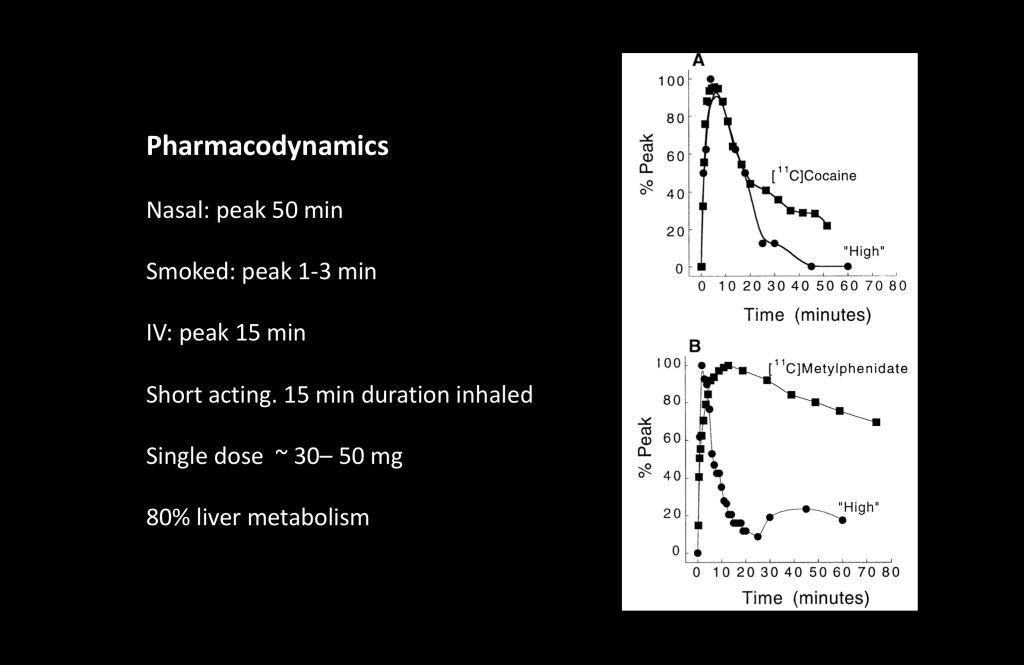

A key property of addictive drugs is hedonic positive reward, the “high” experienced. Subjective high depends more on the rate of distribution than it does on plasma levels. Faster acting drugs result in greater subjective reward.

These experiments conducted at the NIH compared levels of cocaine and methylphenidate (Ritalin) administered intravenously with subjective high. Both result in high dopamine levels. Note that the lower graph, methylphenidate has longer duration in the bloodstream yet the subjective rating falls dramatically after the peak.

Distribution by route of administration to peak level is as follows:

Smoked 1-3 minutes

IV 15 minutes

Nasal 50 minutes

Duration of action is another key factor in addictive potential. Cocaine is a short acting drug with duration of felt effects as low as 15 minutes. Maintaining the effect requires frequent repeat doses. This results in stronger reinforcement behavior and addictive potential. Binge use is common as is poly drug use often combined with alcohol, cannabis, or opiates.

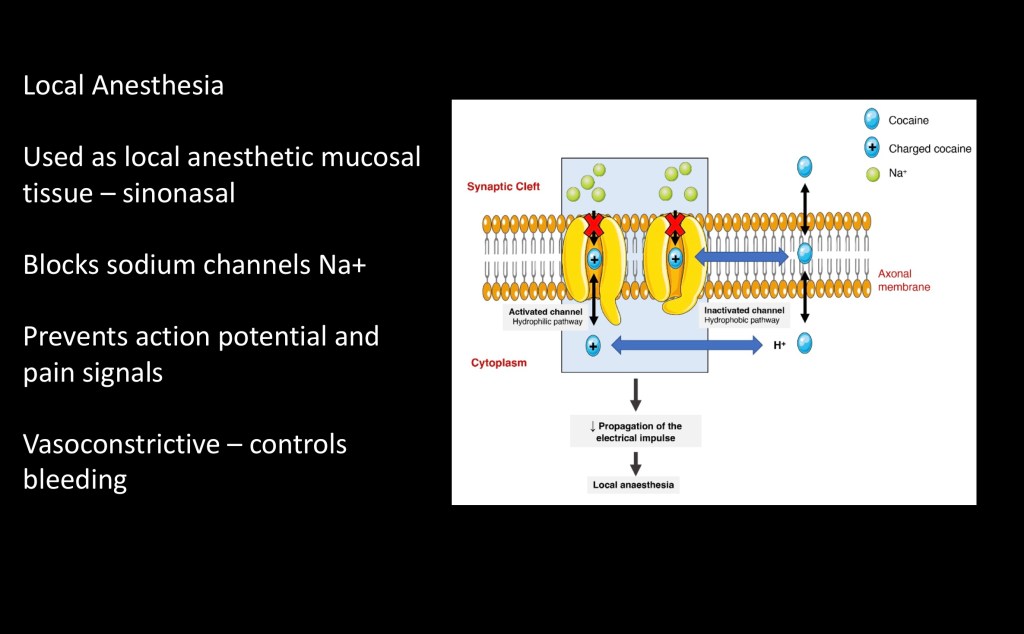

Medicinal use includes local anesthesia primarily in sinonasal procedures as it is readily absorbed through mucosal tissues. It also results in vasoconstriction and reduced bleeding. As there are more effective agents it is rarely used today. Due to vasoconstriction chronic nasal use can result in tissue necrosis and septal perforation.

Anesthetic mechanism is caused by local blockage of ionic sodium Na+ channels at cell membranes. Without flow of positively charged Na+ the nerves cannot generate an action potential. Pain signals are then not conducted further upstream. Note that the cocaine molecule is not destroyed in the process.

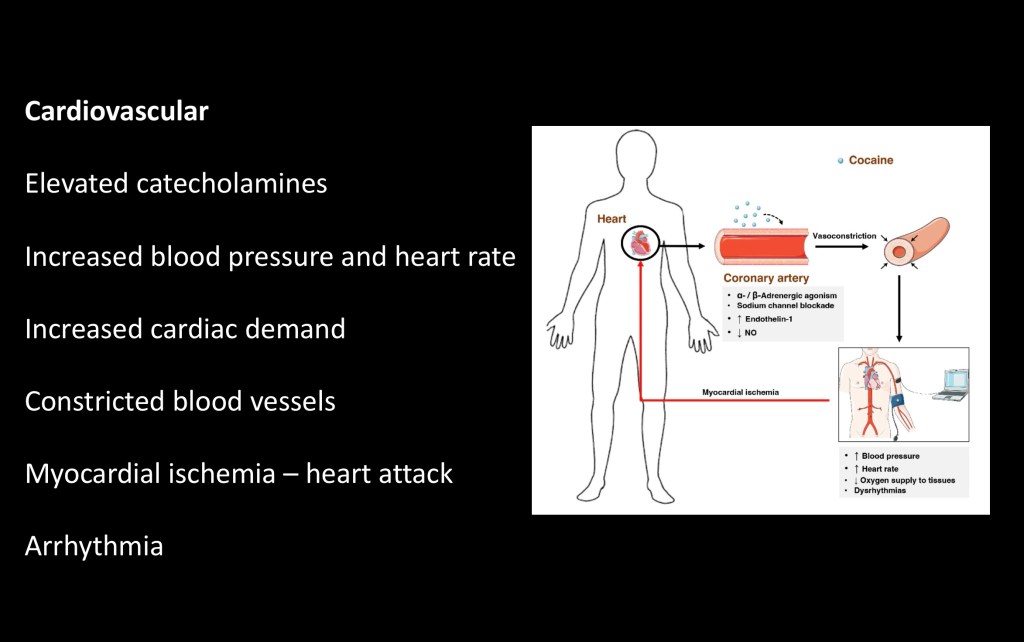

A major risk resulting from cocaine use is to the cardiovascular system. As mentioned above cocaine causes vascular constriction. This narrows arteries including those feeding the heart muscle.

At the same time cocaine results in higher blood levels of catecholamines, the ‘flight or fight’ hormones. This results in increased blood pressure and heart rate. The heart is working harder and at the same time it is getting less blood and oxygen.

The result can be myocardial infarction, a heart attack. This can happen acutely with even a single dose. It can also result in arrhythmia, abnormal heart rhythm due to electrical conduction abnormalities.

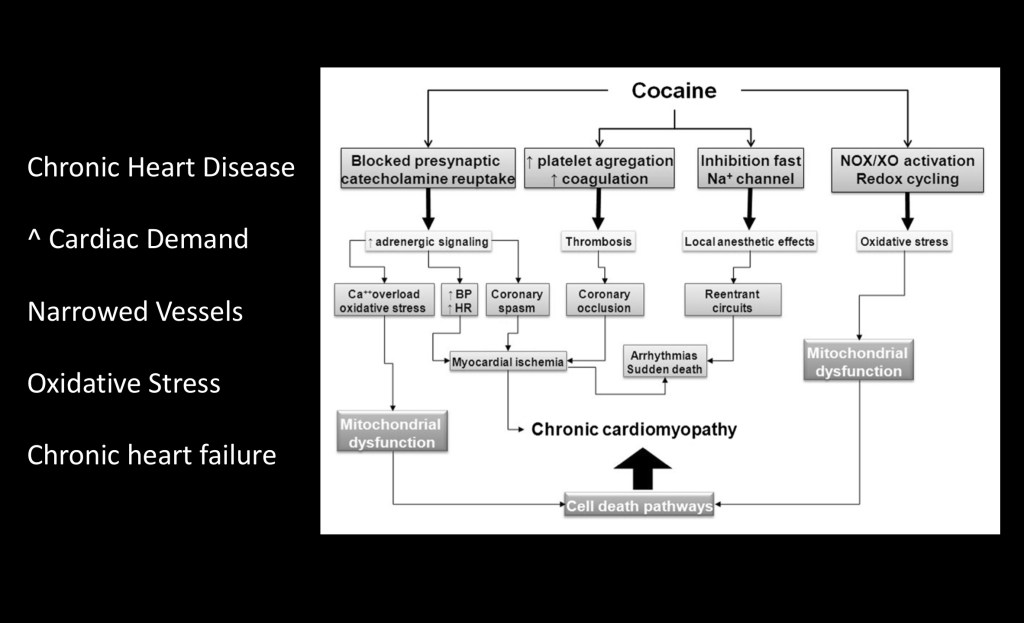

This flow chart illustrates the effects of chronic cocaine use on the heart. By a number of mechanisms the heart muscle is subject to insufficient tissue oxygenation to meet demand resulting in progressively weaker tissue. Metabolic abnormalities result in insufficient energy production by mitochondria. Eventually this can result in irreversible chronic heart failure.

Normal age related changes result in some loss in brain tissue involving both grey matter and white matter. Studies comparing degenerative changes in chronic cocaine users vs matched control subjects have demonstrated marked acceleration of cortical volume loss in cocaine users.

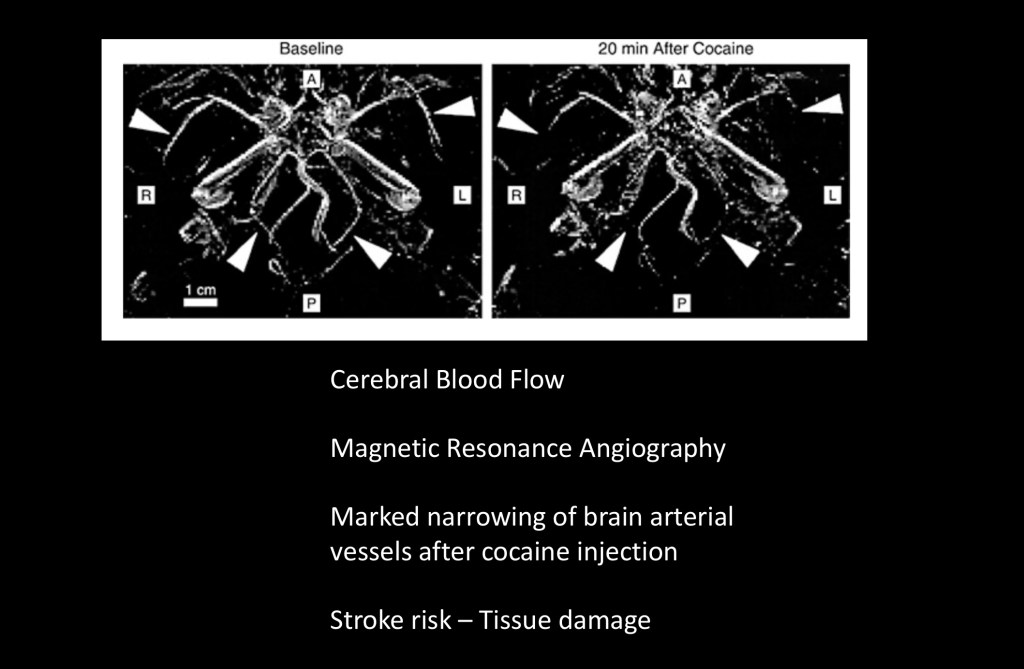

Vascular spasm from acute cocaine use can affect arterial supply to the brain. Above is MR angiography of intracranial circulation. MRA allows visualization of arterial structures due to signal changes in flowing blood.

Normal circulation is on the left. Focus on the arrowheads compared to the image on the right obtained 20 minutes after cocaine injection. The severely narrowed or absent structures are arteries supplying the brain, the PCA and MCA branches. Decreased flow carries risk of clot formation in affected arteries.

Acute cocaine carries the risk of stroke and chronic use gradual tissue loss due to hypoxia.

Central Nervous System

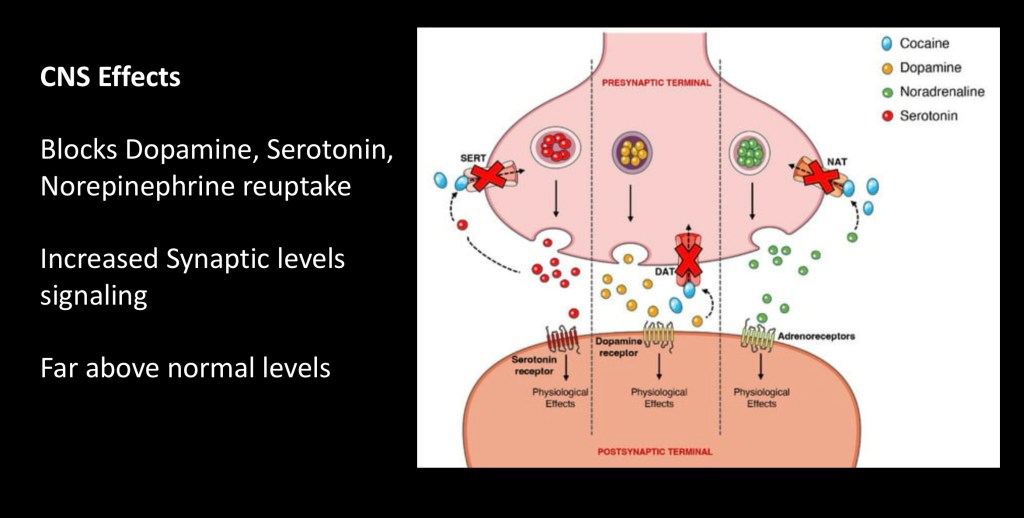

Chemical signaling between neurons is tightly regulated. In response to an action potential the neuron releases stored transmitter, dopamine for example, into the synaptic space. It then docks on an awaiting receptor. The dopamine molecule is released and taken back up by a reuptake transporter to be recycled or broken down. This controls the strength of the signal within normal parameters.

Cocaine blocks reuptake so the neurotransmitter (dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine) hangs around much longer and in greater concentration. This pushes levels far beyond normal limits. Amphetamines also do this although by a different mechanism. Most other drugs such as alcohol or opiates, or natural rewards such as food act indirectly boosting dopamine levels to a lesser extent. SSRI antidepressants are serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

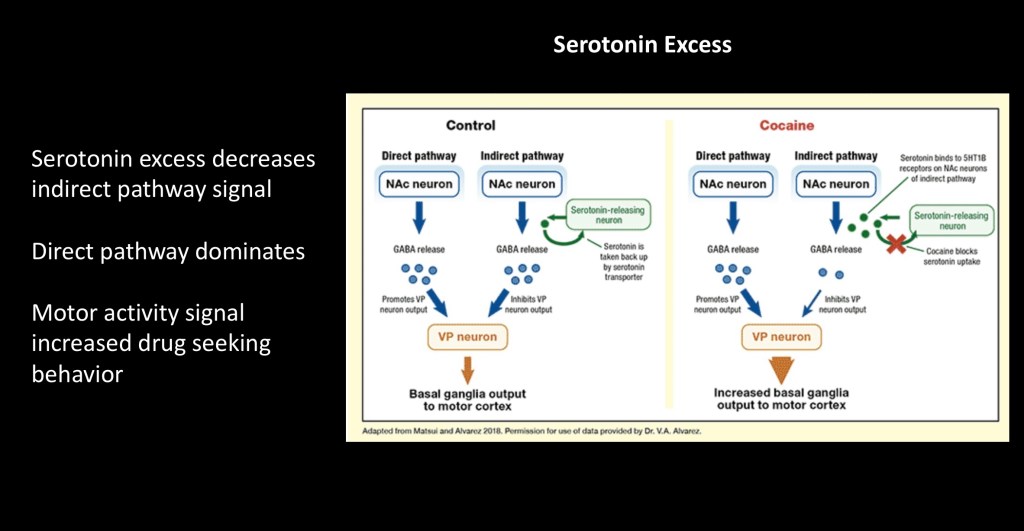

Serotonin is also increased by cocaine. The serotonin system is present in many brain structures and activity varies depending on the receptor type involved.

The above diagram outlines one component affected by serotonin levels in cocaine use. There are two neural circuits regulating an area called the ventral palladium which in turn impacts the basal ganglia and the motor cortex important in initiation and control of purposeful movement.

The indirect and direct pathways balance each other in the normal state. Excess serotonin inhibits the indirect pathway resulting in increased signal from the direct pathway affecting motor movement. This is thought to be important in initiating drug seeking behavior.

The next sections are examples of some research in the frontiers of addiction neuroscience. Before proceeding a few techniques used in laboratory preclinical animal studies are explained.

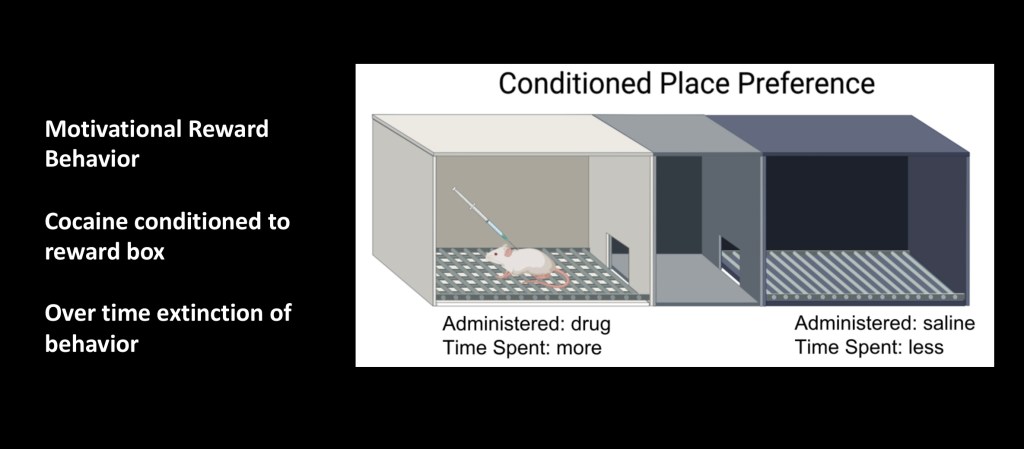

Conditioned place preference is a tool often used in animal models of addiction. The apparatus consists of three compartments. At each end are connected compartments usually differing in color and/or floor pattern. Between them is a compartment where the animal can be placed to choose either room. The animal is first conditioned to the stimulus, cocaine in this case, in one room. Then after a period of abstinence the animal is given a choice of rooms without the reward present. Many variations are possible.

While there is no true animal model of human addiction CPP can replicate the strength of a conditioned behavior and underlying neural changes can be explored.

The following video demonstrates calcium Ca++ fluorescent imaging used in the following experiment.

This technique binds calcium to a fluorescent marker. Calcium flow parallels cellular activation. With a fiber optic probe cellular activation in a precise location can be recorded in real time under experimental conditions.

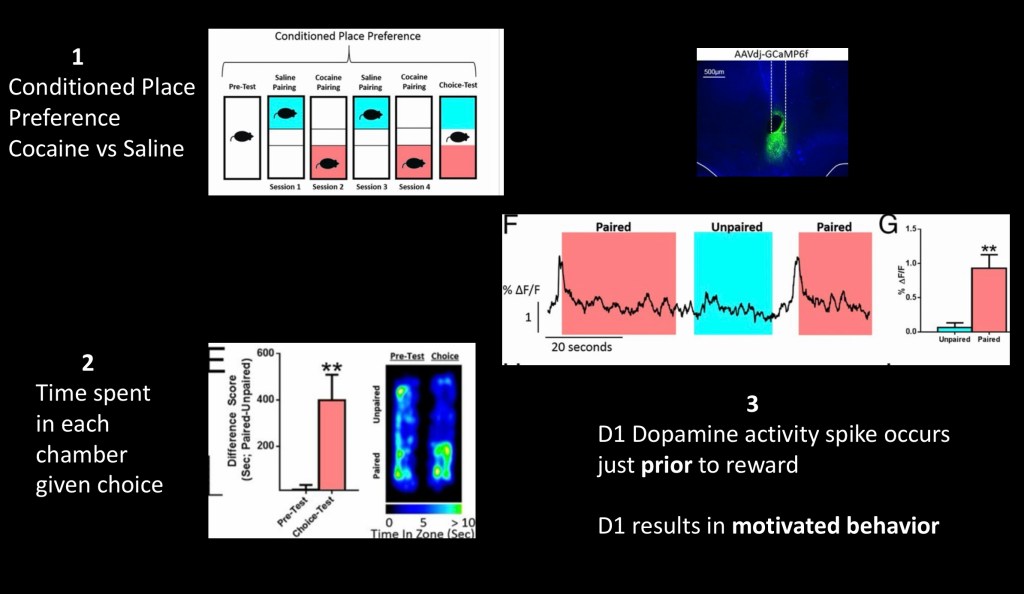

This series of experiments combined the above techniques to further explore the role of dopamine receptor subtypes in addictive behavioral motivation. There are two types of dopamine receptors D1 and D2. This specifically looked at D1 receptors.

- Conditioned place preference. The mouse is given saline in the blue chamber followed by cocaine in the red chamber. After several cycles a choice test without cocaine is performed.

- The blue/green figure is a heat map thermal image representing time the mouse spent in each chamber. It is split between the two chambers before conditioning and nearly all the time is spent in the cocaine chamber after conditioning.

- Tracing represents D1 cellular activity using Ca++ fluorescence. Note that the spike occurs just before entering the cocaine paired chamber and not when in the chamber or in the control saline environment.

The results indicate that D1 dopamine signaling corresponds to cues in anticipation of a drug reward and not to the drug itself. The signal results in drug seeking behavior not simple memory. While a great deal has been learned about biological changes occurring in substance addiction attention is shifting to more detailed investigation into drug cues and triggers and longer term changes contributing to relapse risk.

Epigenetics refers to cellular mechanisms regulating DNA expression in response to changes in the environment. Every cell in our bodies carries the same set of DNA instructions. Immediately after conception the cells differentiate as they develop into separate cell types and tissues, muscle, neurons, fat cells, and so on. This involves a complex cascade of events turning on or off specific genes in response to signaling molecules in and around the cells.

This continues throughout life and neurons are highly adaptable changing, growing or shrinking in response to the environment. Many Epigenetic changes are long term and may pass from generation to generation. A great deal about these mechanisms is still unknown.

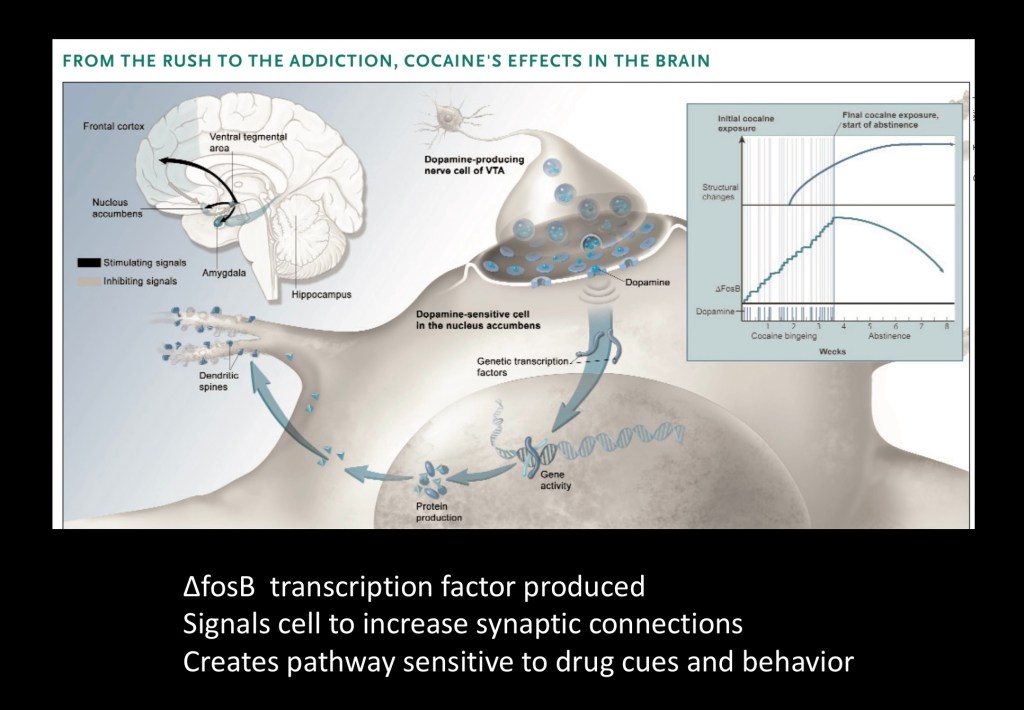

The above diagram represents a neuron in the nucleus accumbens receiving a dopamine signal. This activates a gene producing the regulatory protein ΔfosB. This protein activates other genes causing the cell to grow new dendrites and synaptic connections. The graphs in the upper right show that this process continues after the drug is discontinued. So addictive drugs create new pathways in the brain which persist after detox and into recovery.

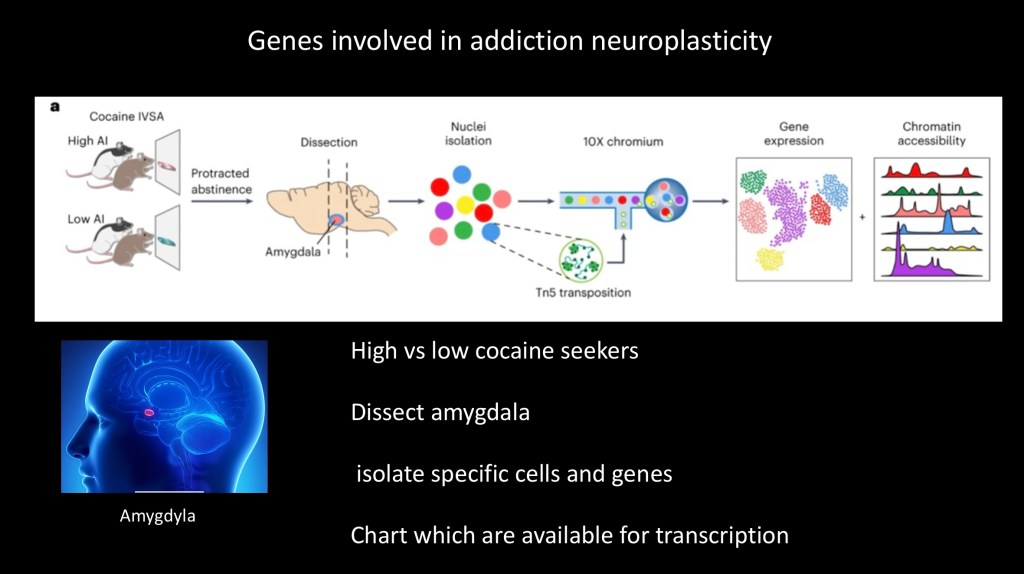

Much about the specific molecular signaling and genes involved in addiction is still unknown. This experiment sought to identify and create a database of candidate genes involved in cocaine addiction.

Rats bred for high and low drug seeking behavior were used. Following cocaine administration and abstinence. DNA obtained from the amygdala was separated for analysis. The amygdyla is well known to have a key role in addiction pathology.

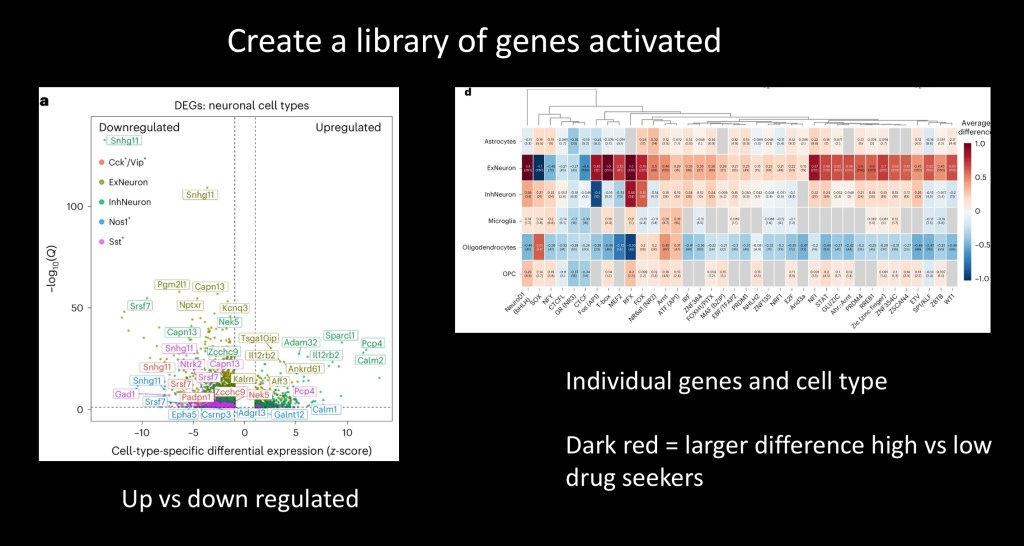

The chart on the left shows specific individual genes available and in the upregulated or down regulated configuration.

On the right the genes found are on the horizontal axis and the brain cell type in which they are found on the vertical axis. Color corresponds to differences in expression between high and low drug seeking strains. Dark red indicates a stronger difference and greater chance that the gene is involved in addictive behavior.

This example illustrates how more sophisticated tools and techniques are being employed to find precise molecular pathways involved in addiction. The hope is that medications can then be developed to aid in treatment. There are no current medications currently available for treatment of cocaine addiction. Epigenetics is a potential target and chemotherapy targeting epigenetics is currently used in cancer treatment.

This study used fMRI to evaluate connectivity between the frontal lobe and other regions of the brain including the hippocampus, striatum, amygdyla, and temporal insula in chronic cocaine users. Connectivity was measured in the resting state without external stimuli.

Decreased connectivity was found between these regions in cocaine users in comparison to controls. Degree of connectivity loss corresponded to amount of intake and progressive loss of control over consumption. Psychometric testing demonstrated a positive correlation with trait impulsivity.

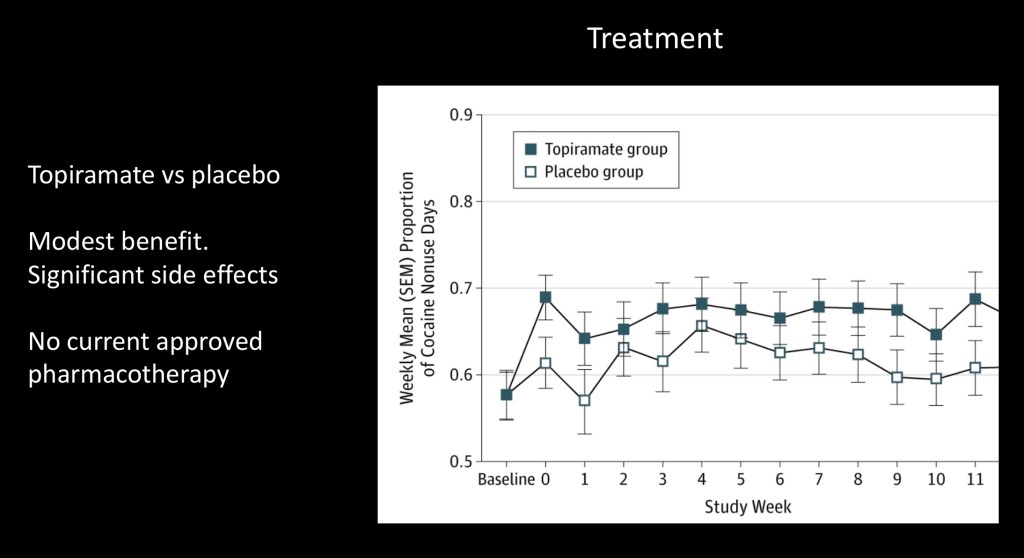

A number of medications have been studied as potentially therapeutic in treatment of cocaine addiction. This placebo controlled study looked at Topiramate, a GABA acting agent used in epilepsy and for migraine prevention. Standard psychotherapy was also provided. Modest improvement was noted in the topiramate group. Given potential side effects it has not been adapted for clinical use.

A number of agents have been seen as promising including dopamine agonists, long acting amphetamines, a vaccine, Modafinil, and methylphenidate. None of these have found to be clinically useful. Psychotherapy, Cognitive behavioral therapy, and peer support groups are available treatment options. Withdrawal from cocaine can be distressing with mood changes, sleep disturbances, irritability, and intense cravings commonly experienced. Withdrawal symptoms are generally not medically dangerous.

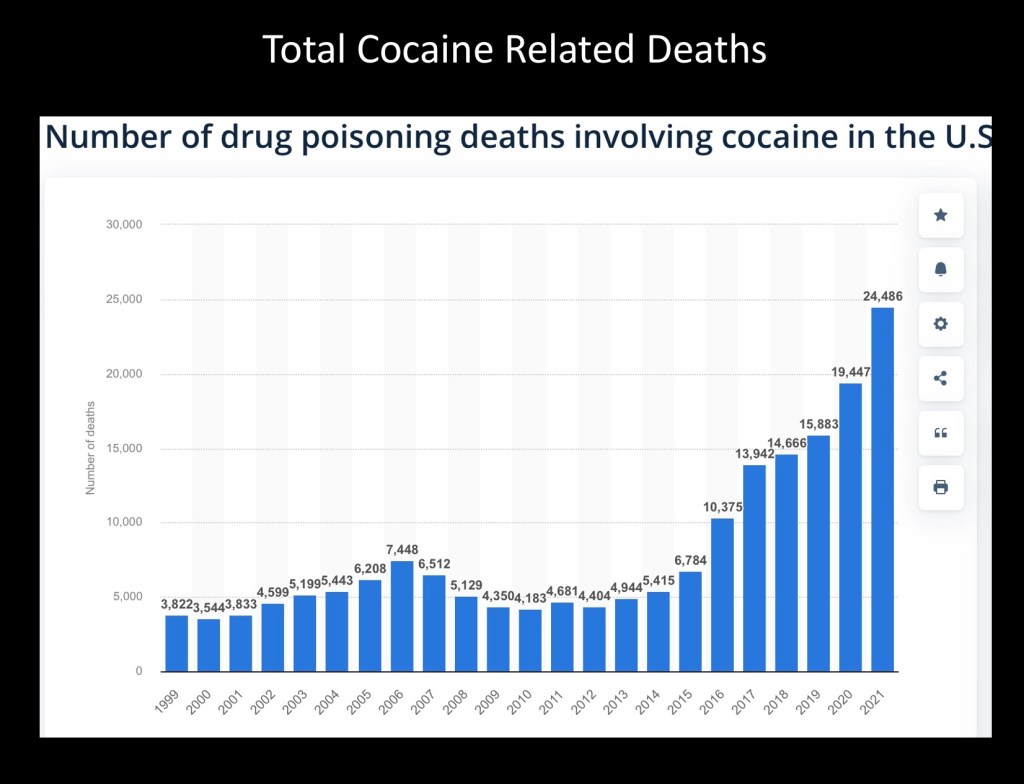

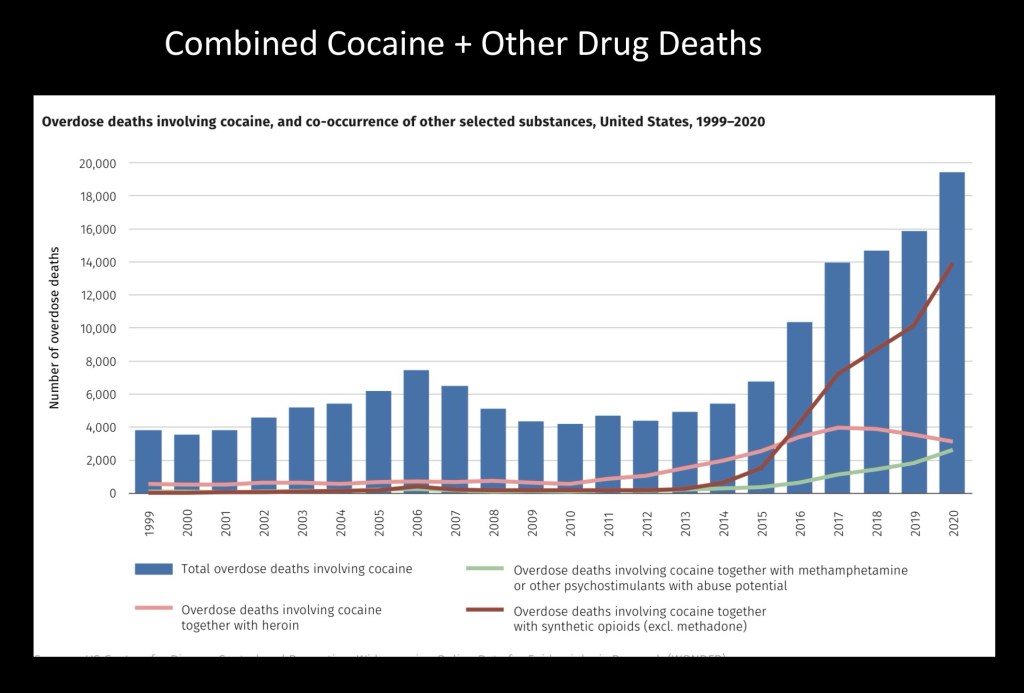

Total deaths involving cocaine have significantly increased over the past decade and increasing each year. Global production due to record crop yields, improved extraction methods and distribution changes reaching new markets are increasing overall available supply.

The majority of cocaine related deaths involve multi drug use particularly added fentanyl which accounts for the majority of drug overdoses and deaths since about 2014.

…………………………………………………………………………………………..

Reported use of cocaine has increased nearly 400% in the past decade. Despite efforts there has been little advance in developing more effective treatments for cocaine addiction. Current efforts are focused on epigenetics and neuroplasticity associated with addictive behavior and relapse risk.

The movie Cocaine Bear is loosely based on a true story. In 1985 in a national forest in northern Georgia a deceased 175lb black bear was found by a hiker. Evidence at the scene and post mortem toxicology concluded that the bear had died of cocaine overdose presumably lost by smugglers or dropped from a plane.

For education and information purposes only. Images and data obtained from sources freely available on the world wide web. This post should not be considered medical or professional advice. Feedback and comments are always welcome.

Jeff Kay 2/2024

References

Single-nucleus genomics in outbred rats with divergent cocaine addiction-like behaviors reveals changes in amygdala GABAergic inhibition

Jessica L. Zhou, Giordano de Guglielmo, Aaron J. Ho, Marsida Kallupi, Nar

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-023-01452-y

………………………………………………………………

Addiction to Cocaine and Amphetamine

Steven E. Hyman*

Laboratory of Molecular and Developmental Neuroscience

Massachusetts General Hospital

Harvard Medical School

Boston, Massachusetts 02114

Neuron, Vol. 16, 901–904, May, 1996, Copyright 1996 by Cell Press

………………………………………………………………………

John R. Richards, Dariush Garber, Erik G. Laurin, Timothy E. Albertson, Robert W. Derlet, Ezra A. Amsterdam, Kent R. Olson, Edward A. Ramoska & Richard A. Lange (2016) Treatment of cocaine cardiovascular toxicity: a systematic review, Clinical Toxicology, 54:5, 345-364, DOI: 10.3109/15563650.2016.1142090

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2016.1142090

……………………………………………………………………………

Cocaine: An Updated Overview on Chemistry, Detection, Biokinetics, and Pharmacotoxicological Aspects including Abuse Pattern

Toxins 2022, 14(4), 278; https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14040278

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/14/4/278

…………………………………………………………………………….

Cocaine Self-Administration Produces Pharmacodynamic Tolerance: Differential Effects on the Potency of Dopamine Transporter Blockers, Releasers, and Methylphenidate

Mark J Ferris, Erin S Calipari, Yolanda Mateo, James R Melchior, David CS Roberts & Sara R Jones

https://www.nature.com/articles/npp201217

……………………………………………….

Imaging studies on the role of dopamine in cocaine reinforcement and addiction in humans

Nora D.Volkow1, Joanna S. Fowler2 and Gene-Jack Wang1 12

Departments of Medicine and Chemistry, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NewYork, NY 11973, USA.

Journal of Psychopharmacology 13(4) (1999) 337±345

81999 British Association for Psychopharmacology (ISSN 0269-8811)

………………………………………………………………….

2 minute neuroscience cocaine

………………………………………………………………….

Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology

Manuscript version of

Pharmacological Validation of a Translational Model of Cocaine Use Disorder: Effects of d-Amphetamine Maintenance on Choice Between Intravenous Cocaine and a Nondrug Alternative in Humans and Rhesus Monkeys

Joshua A. Lile, Amy R. Johnson, Matthew L. Banks, Kevin W. Hatton, Lon R. Hays, Katherine L. Nicholson,

2019, American Psychological Association.

………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………….

Stimulant Abuse: Pharmacology, Cocaine, Methamphetamine, Treatment, Attempts at Pharmacotherapy

Daniel Ciccarone, MD, MPH[Associate Professor]

Co-Director, Foundations of Patient Care, Department of Family and Community Medicine,

Prim Care. 2011 March ; 38(1): 41–58. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2010.11.004.

………………………………………………………………………………

Translating the atypical dopamine uptake inhibitor hypothesis toward therapeutics for treatment of psychostimulant use disorders

- Amy Hauck Newman, Jianjing Cao, Jacqueline D. Keighron, Chloe J. Jordan,

Neuropsychopharmacology volume 44, pages 1435–1444 (2019

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-019-0366-z

………………………………………………………………………

Cocaine Cues and Dopamine in Dorsal Striatum: Mechanism of Craving in Cocaine Addiction

Nora D. Volkow,1 Gene-Jack Wang,2 Frank Telang,1 Joanna S. Fowler,3 Jean Logan,3 Anna-Rose Childress,4

Millard Jayne,1 Yeming Ma,1 and Christopher Wong3

1National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda Maryland 20892, 2Medical Department and 3Department of Chemistry, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York 11973, and 4Department of Psychiatry,

The Journal of Neuroscience, June 14, 2006 • 26(24):6583– 6588 • 6583

Mechanism and Time Course of Cocaine-Induced Long- Term Potentiation in the Ventral Tegmental Area

Emanuela Argilli,1,2 David R. Sibley,3 Robert C. Malenka,4 Pamela M. England,5,6 and

The Journal of Neuroscience, September 10, 2008 • 28(37):9092–9100

………………………………………………………….

https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/chronic-cocaine-use-may-speed-up-ageing-of-brain

…………………………………………………………..

The Neurobiology of Cocaine Addiction

Eric J. Nestler, M.D., Ph.D.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Dallas, Texas

SCIENCE & PRACTICE PERSPECTIVES—DECEMBER 2005

……………………………………………………………

Role of serotonin in cocaine effects in mice with reduced dopamine transporter function

Yolanda Mateo, Evgeny A. Budygin, Carrie E. John, and Sara R. JonesAuthors Info & Affiliations

December 22, 2003

101 (1) 372-377

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0207805101

………………………………………………………….

https://www.cnn.com/2022/12/03/movies/cocaine-bear-true-story-trailer-trnd/index.html

…………………………………………………

Neuroplasticity in the mesolimbic dopamine system and cocaine addiction

MJ Thomas1,2, PW Kalivas3 and Y Shaham4

1Department of Neuroscience, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA;

British Journal of Pharmacology (2008) 154, 327–342; doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.77; published online 17 March 2008

https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1038/bjp.2008.77

……………………………………………………..

Role of serotonin in cocaine effects in mice with reduced dopamine transporter function

Yolanda Mateo, Evgeny A. Budygin, Carrie E. John, and Sara R. JonesAuthors Info & Affiliations

December 22, 2003

101 (1) 372-377

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0207805101

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0207805101

………………………………………………………

In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward

Erin S. Calipari, Rosemary C. Bagot, Immanuel Purushothaman, +8 , and Eric J. Nestlereric.nestler@mssm.edu

National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved January 8, 2016 (received for review October 27, 2015)

February 1, 2016

113 (10) 2726-2731

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521238113

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1521238113

…………………………………………………………………………….

Ca++ imaging

……………………………………………………………………………..

Cocaine: history, use, abuse

R Soc Med 1999;92:393-39 SECTION OF CLINICAL FORENSIC & LEGAL MEDICINE, 20 JUNE 1998

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/014107689909200803

Risk of Becoming Cocaine Dependent: Epidemiological Estimates for the United States, 2000–2001

Megan S O’Brien & James C Anthony

https://www.nature.com/articles/1300681

……………………………………………………………..

…………………………………………………………………..

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Rewarding Effects of Cocaine

F. SCOTT HALL,a ICHIRO SORA,b JANA DRGONOVA,a XIAO-FEI LI,a MICHELLE GOEB,a AND GEORGE R. UHLa

aMolecular Neurobiology Branch, NIDA-IRP, NIH/DHHS, Baltimore, Maryland 21224,

bTohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Neuroscience

……………………………………………………………

Pathophysiological mechanisms of catecholamine and cocaine-mediated cardiotoxicity

Lucas Liaudet • Belinda Calderari •

Heart Fail Rev (2014) 19:815–824 DOI 10.1007/s10741-014-9418-y

…………………………………………………………………

Data Available on the Extent of Cocaine Use and Dependence: Biochemistry, Phar- macologic Effects and Global Burden of Disease of Cocaine Abusers

C. Pomara*,#,1, T. Cassano#,2, S. D’Errico1, S. Bello1, A.D. Romano3, I. Riezzo1 and G.

1Institute of Forensic Pathology, Department of Experimental and Clinical Sciences; 2Institute of Pharmacology, Department of Experimental and Clinical Sciences; 3Insti

Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2012, 19, 5647-5657

………………………………………………………………………….

A National Evaluation of Treatment Outcomes for Cocaine Dependence

D. Dwayne Simpson, PhD; George W. Joe, EdD; Bennett W. Fletcher, PhD; et al

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(6):507-514. doi:10-1001/pubs.Arch Gen Psychiatry-ISSN-0003-990x-56-6-yoa8260

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/1673778

……………………………………………………………………..

The Neuropsychiatry of Chronic Cocaine Abuse

Karen I. Bolla, Ph.D. Jean-Lud Cadet, M.D. Edythe D. London, Ph.D.

The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 1998; 10:280–28

https://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/jnp.10.3.280

……………………………………………………………………….

KYLE M. KAMPMAN HTTPS://ORCID.ORG/0000-0002-9760-8324

The treatment of cocaine use disorder

KYLE M. KAMPMAN HTTPS://ORCID.ORG/0000-0002-9760-8324

https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/sciadv.aax1532

………………………………….

Environmental, genetic and epigenetic contributions to cocaine

addiction

R. Christopher Pierce , Bruno Fant , Sarah E. Swinford-Jackson , Elizabeth A. Heller , Wade H. Berrettini and Mathieu E. Wimme

Neuropsychopharmacology (2018) 43:1471–1480; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0008-x

……………………………………………………..

Molecular genetics of cocaine use disorders in humans

Noèlia Fernàndez-Castillo, Judit Cabana-Domínguez, Roser Corominas & Bru Cormand

Molecular Psychiatry volume 27, pages 624–639 (2022)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-021-01256-1

Cocaine: An Updated Overview on Chemistry, Detection, Biokinetics, and Pharmacotoxicological Aspects including Abuse Pattern

Rita Roque Bravo 1,2,†, Ana Carolina Faria Andreia Machado Brito-da-Costa Helena Carmo

Toxins 2022, 14,278. https://doi.org/10.3390/

…………………………………………………………..

How Cocaine Cues Get Planted in the Brain

NIH

……………………………………………………………..

R HDAC5 and Its Target Gene, Npas4, Function in the Nucleus Accumbens to Regulate Cocaine-Conditioned Behaviors

Makoto Taniguchi 1 , Maria B Carreira 2 , Yonatan A Cooper

. 2017 Sep 27;96(1):130-144.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.015.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28957664/

…………………………………………………… ………….

…………………………………………………………………………..

Serotonin at the Nexus of Impulsivity and Cue Reactivity in Cocaine Addiction

Kathryn A. Cunningham and Noelle C. Anastasio

Center for Addiction Research and Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, 77555, U.S.A.

Neuropharmacology. 2014 January ; 76(0 0): 460–478. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.06.030.

…………………………………………………………………………..

December 2013

Topiramate for the Treatment of Cocaine Addiction

A Randomized Clinical Trial

Bankole A. Johnson, DSc, MD1,2; Nassima Ait-Daoud, MD1; Xin-Qun Wang, MS3;

JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1338-1346. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2295

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/article-abstract/1756816

………………………………………………………………………………..

Cocaine Cues and Dopamine in Dorsal Striatum: Mechanism of Craving in Cocaine Addiction

Nora D. Volkow,1 Gene-Jack Wang,2 Frank Telang,1 Joanna S. Fowler,3 Jean Logan,3 Anna-Rose Childress,4

Millard Jayne,1 Yeming Ma,1 and Christopher Wong3

1National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda Maryland 20892, 2Medical Department and 3Department of Chemistry, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York 11973, and 4Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

The Journal of Neuroscience, June 14, 2006 • 26(24):6583– 6588 • 6583

………………………………………………………………………………………

Nucleus accumbens feedforward inhibition circuit promotes cocaine self-administration

Jun Yu, Yijin Yan, King-Lun Li, +5 , and Yan Dong yandong@pitt.eduAuthors Info & Affiliations

Edited by Susan G. Amara, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved August 29, 2017 (received for review May 11, 2017)

September 25, 2017

114 (41) E8750-E8759

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707822114

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1707822114

………………………………………………………………………………………..

June 2015

Impaired Functional Connectivity Within and Between Frontostriatal Circuits and Its Association With Compulsive Drug Use and Trait Impulsivity in Cocaine Addiction

Yuzheng Hu, PhD1; Betty Jo Salmeron, MD1; Hong Gu, PhD1; et al

JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):584-592. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2212253

……………………………………………………………………….

February 4, 1998

Cocaine-Induced Cerebral Vasoconstriction Detected in Humans With Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Marc J. Kaufman, PhD; Jonathan M. Levin, MD, MPH; Marjorie H. Ross, MD; Nicholas Lange, ScD; Stephanie L. Rose; Thellea J. Kukes; Jack H. Mendelson, MD; Scott E. Lukas,

JAMA. 1998;279(5):376-380. doi:10.1001/jama.279.5.376

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/187198

……………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………….

Leave a comment