Incentive Sensitization

Previous posts in this series have focused on key biological processes occurring as use of addictive substances progresses from early exploratory use through habitual and compulsive addiction.

There are three lines of investigation resulting in what is now the dominant model understood as addiction as a brain disorder with identifiable pathological neuro adaptive abnormalities corresponding to key psychological, cognitive, and behavioral patterns.

The reward/reward deficit model focuses on the dopaminergic system and downstream effects on cognitive frontal lobe centers important in salience, executive function, and cognitive processing. Positive reinforcement diminishes over time requiring more frequent use.

The opponent process anti reward model describes persistent stress related hyperactivity in the amygdala and hypothalamus resulting in allostasis, a negative affective set point. Use is driven by negative reinforcement in an effort to attenuate negative consequences. Koob and LeMond have been the primary investigators along this line.

This post focuses on the incentive sensitization model. It has been primarily developed by Kent Berridge and Terry Robinson in their labs at University of Michigan. It explains heightened motivational behavior in response to drug related cues and explains drug cravings and risk of relapse following detoxification.

These three theories are not in conflict. They can be incorporated in a model in which all three are occurring in parallel in a continuing addiction cycle.

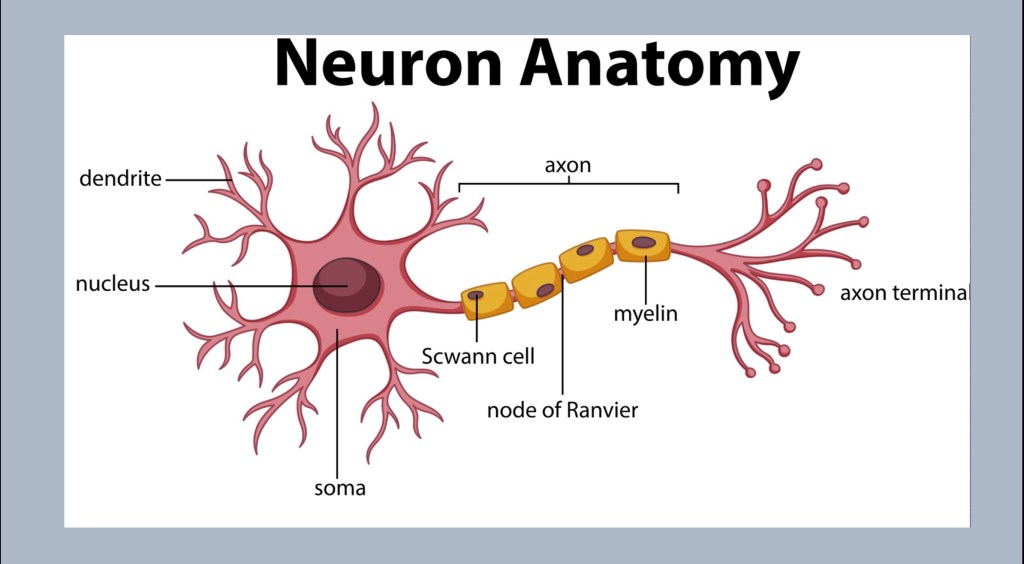

The neuron is the basic unit of the nervous system. Neurons are highly specialized in form and function localized to specific regions. However they all have the same components.

Cell Body – Neurons have a nucleus containing DNA. They have the apparatus for protein synthesis, metabolism, repair and other functions. Neurons are highly responsive to environmental cues. They can grow new components. One thing they cannot do is reproduce. Once cell death has occurred the tissue cannot be replaced.

Dendrites – The receiving arms of the cell. Depending on the type of cell there can be a few or many thousands of these. Dendrites are gained or lost in response to conditions.

Axon – The axon is where the signal is transmitted from one place to the next. These can be as short as a millimeter in length to a meter or more. The signal is propagated as an action potential. This is an electrical impulse driven my ion flux across the cell membrane. They may be surrounded by a myelin sheath.

Axon Terminal – At the transmitting ends. Neurotransmitter is stored here to be released when a signal is received.

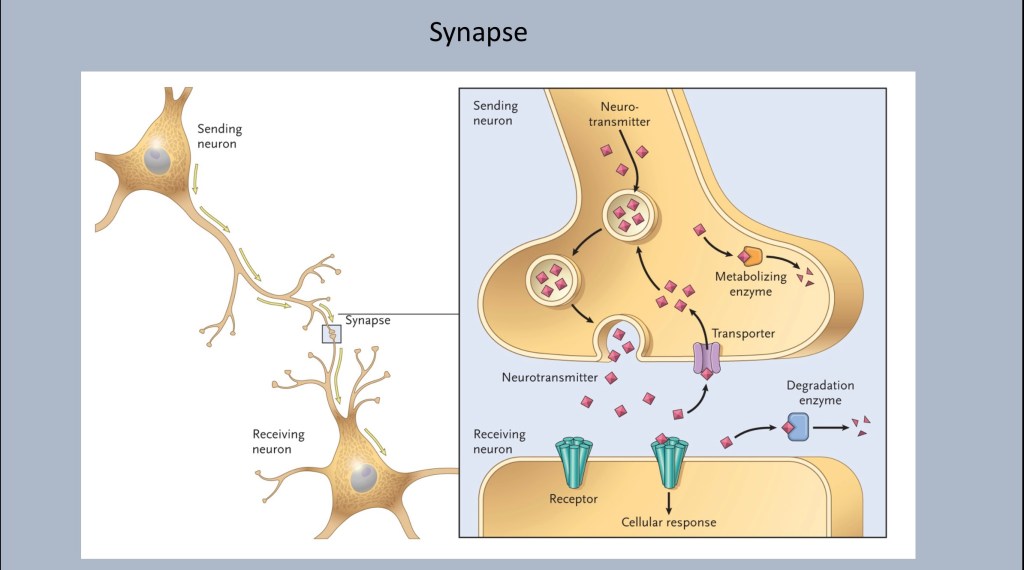

A closer look at the synapse between neurons.

Neurotransmitters are stored in vesicles to be released into the synaptic space when the appropriate signal arrives. Each neuron is specialized to produce and release a specific neurotransmitter. These can be excitatory or inhibitory.

Waiting in the membrane of the receiving cell are receptors specific for a given transmitter. The transmitter, dopamine or glutamate for example, docks at the receptor. It does not enter the cell. When it is released it is taken back up to be recycled or broken down by a transporter protein.

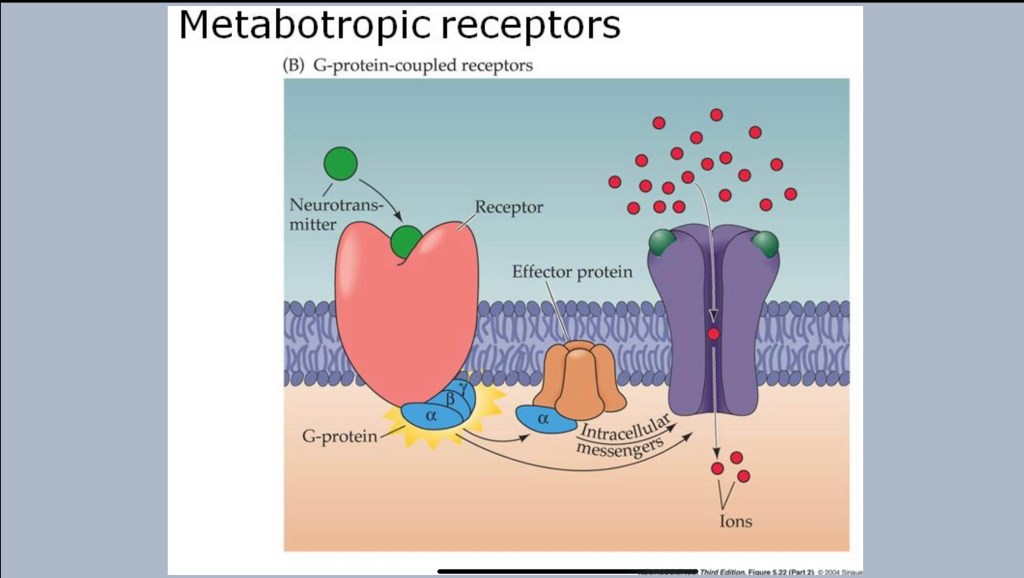

A closer look at receptors.

The cell membrane is a very tight barrier. When a receptor is activated a series of chemical reactions occur which affect cell functions. An excitatory signal from glutamate for example will result in opening of an ion channel. Charged ions such as Sodium, Calcium, or Chloride (Na+, K+, Cl-) rush in or out resulting in an electric current down the axon.

There are different types and subtypes of receptors and a cell may receive inputs from a number of different cell types with opposing activity. Thus what happens downstream is a highly dynamic process.

Looking back out at the brain and changes occurring in addiction.

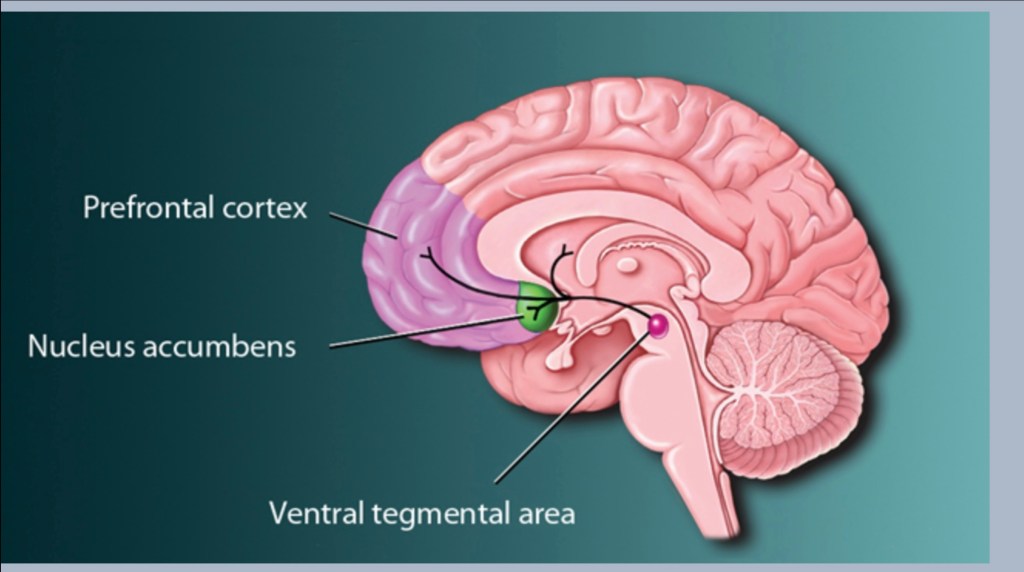

The dopamine reward pathway is a relatively small area located at the center of the brain. The pathway is forward firing. It can be thought of as a one way road extending from the ventral Tegmental area in the midbrain to an almond shaped structure, the nucleus accumbens. There are additional side roads to the frontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus.

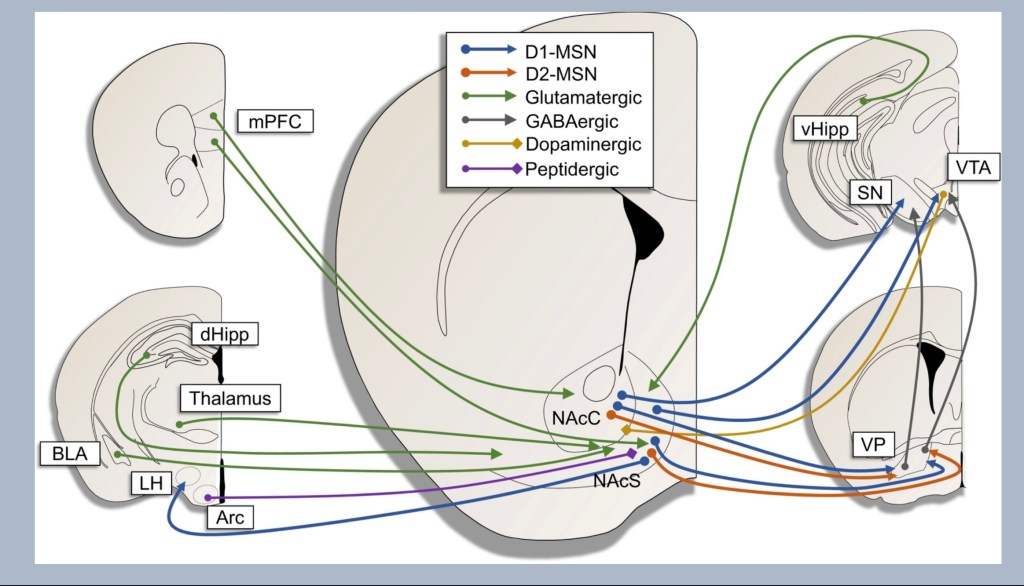

If the reward pathway is a one way street the nucleus accumbens is the Dallas-Ft.Worth airport. This is a central crossroads and a very busy crowded focal point. The NAC is where signals from various parts of the brain meet and are processed.

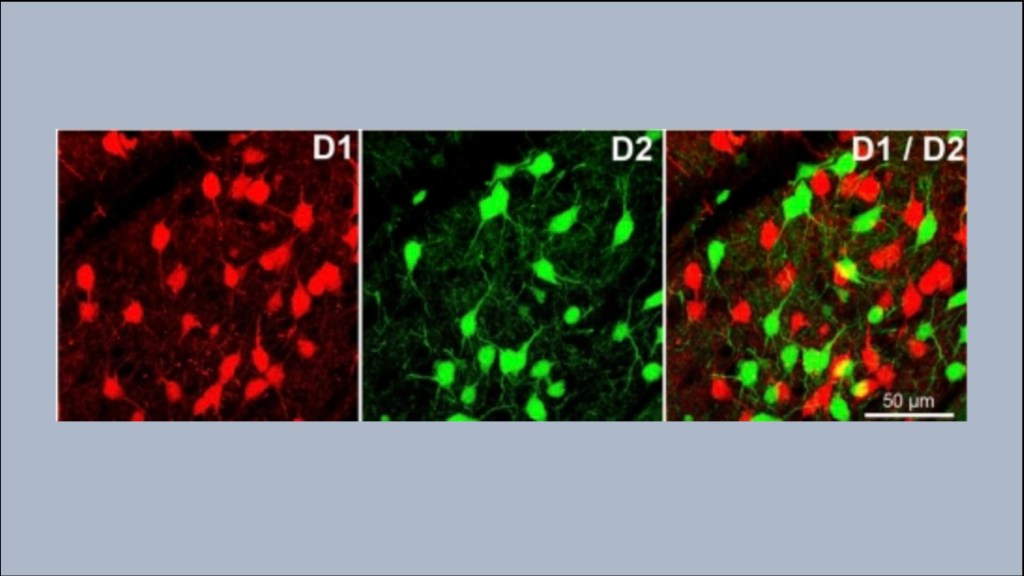

The key at the top color codes the transmitter types involved. D1 and D2 MSN refer to dopamine receptor (not transmitter) subtypes expressed on Medium Spiny Neurons. These are inter neurons receiving signals, processing them, and sending them out to various regions of the brain. If you were to choose one cell most important in addiction it would be these neurons.

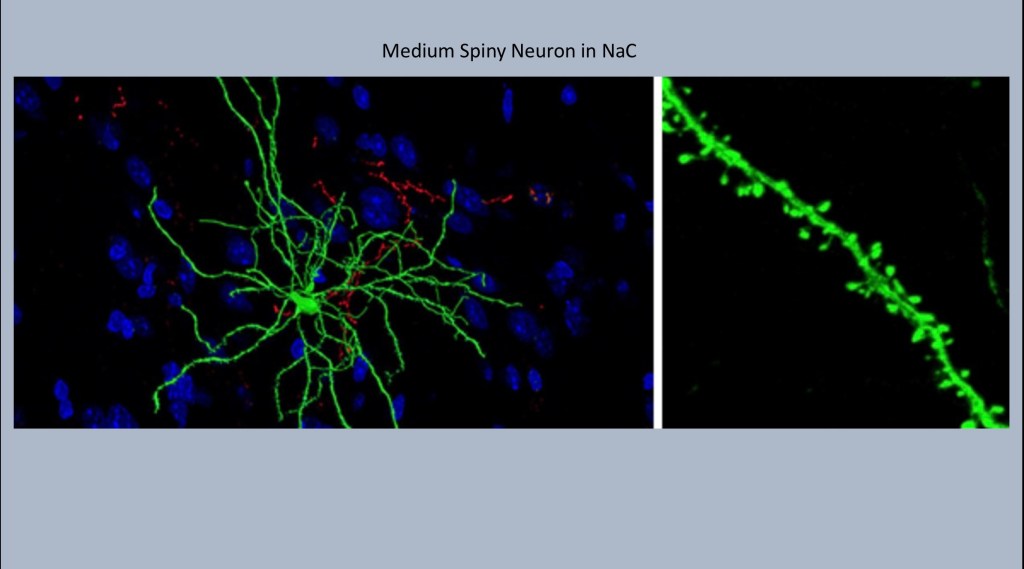

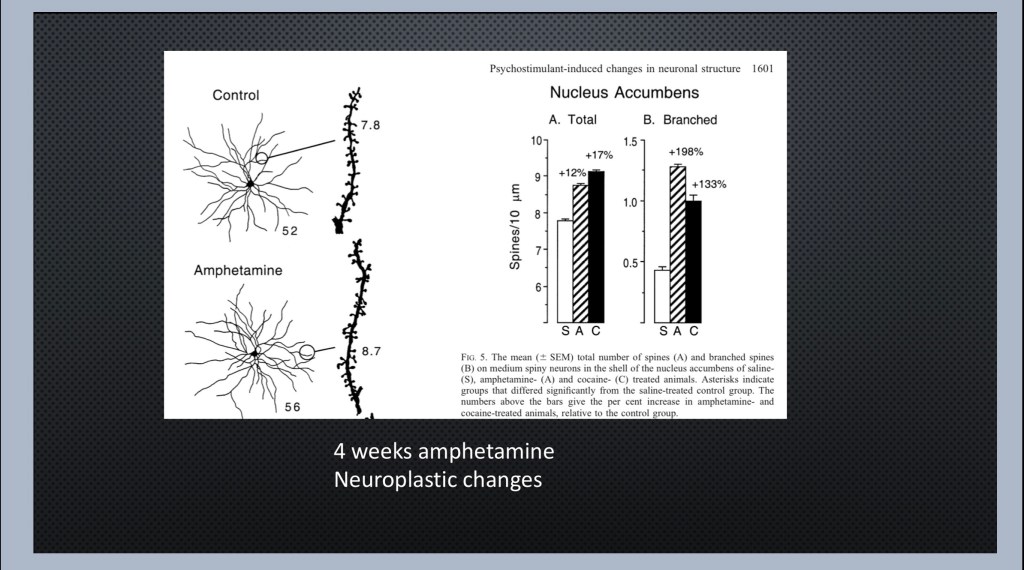

Medium Spiny Neurons shown here inhabit the nucleus accumbens. Each one may receive synaptic input from up to 10,000 neurons. The name comes from these tiny knobby spines projecting along the dendrites. Each spine represents a synaptic connection with an adjacent neuron.

In response to repeated exposure to an addictive drug the number and density of dendritic spines increases and dendrites grow more branches. Thus the cells become more responsive and sensitized to incoming signals. This is a key change in the addictive process. The drug itself and other related cues can stimulate increased cellular activity.

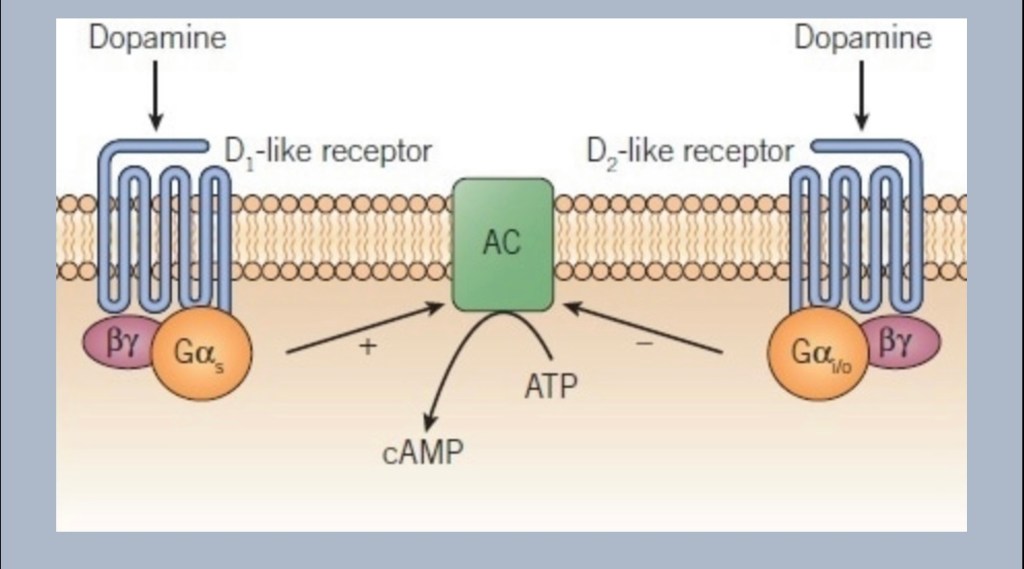

This is a second change occurring in the cells of the nucleus accumbens. Medium spiny neurons have one of two different subtype groups of dopamine receptors D1 or D2. When dopamine docks on a D1 receptor the cell reacts differently than a D2 type. The diagram shows D1 activity promoting formation of the messaging intermediary cAMP and D2 inhibiting it. D1 neurons respond to rapid bursts of dopamine (phasic) whereas D2 neurons respond to steady state (tonic) dopamine levels.

Under normal conditions D1 and D2 effects are in balance. This allows for appropriate responses to changing conditions. Over time as addiction drives neurotransmitter levels higher there is a shift in receptor types. Fewer D2 receptors are expressed and D1 receptors predominate. This has been demonstrated in humans and animal models to result in increased drug seeking behavior and responses to drug related cues.

In animals for example when D2 receptors are blocked the mice will work harder to obtain a reward, they will expend increased activity to seek out reward. In “knockout” mice lacking D1 receptors the mice will fail to initiate drug seeking behaviors. Similar results have been demonstrated in human subjects responding to drug related cues.

These changes on a cellular level have been shown to correspond with focused elevated incentive salience and motivation. This refers to increased effort and desire to obtain a given reward.

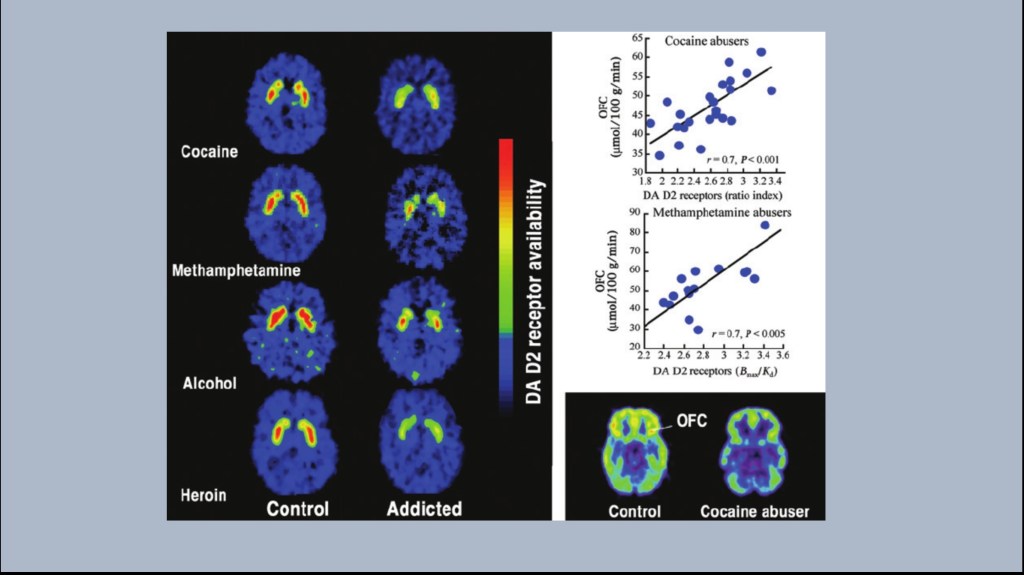

This series of experiments performed in Nora Volkow’s lab at the NIH was among the first to demonstrate this change in human subjects. These are PET scans comparing control subjects with detoxed individuals addicted to the labeled substances.

A radioactive agent (11C raclopromide) was injected which binds selectively to D2 receptors. Red indicates more receptors.

The areas of increased activity are in the striatum located within the reward pathway and rich in dopamine neurons.

As shown above the test subjects demonstrated fewer D2 receptors compared to controls even without the drug present. This same finding occurs despite entirely different mechanisms of action of these addictive drugs. Additional imaging has demonstrated partial to complete receptor recovery within about 2 years of abstinence.

On the right graphs demonstrate a linear relationship between loss of D2 receptors in the reward pathway and decrease of glucose metabolism in the frontal cortex. These abnormalities are linked as the addictive process continues.

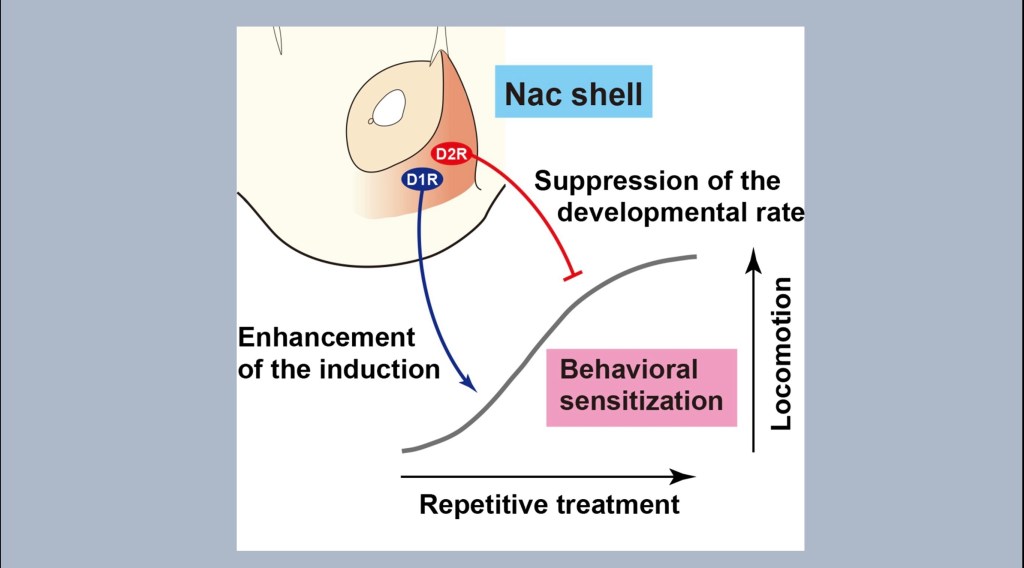

The diagram illustrates the effect of shift to D1 predominance. With repetitive treatment using the same dose observed locomotor activity such as multiple lever presses to receive reward increases. This effect increases with D1 predominance and decreases with D2 predominance.

This process is known as sensitization. Sensitization results from a specific stimulus rather than an overall general increased reactivity.

In addiction the individual becomes more reactive to specific drug cues and less motivated to seek out other rewarding stimuli.

A key concept in this theory is the distinction between “liking” and “wanting”. People studying addiction previously assumed that increased consumption of addictive substances occurred because certain individuals abnormally liked and were attracted to the drug.

That is not what occurs. As the addiction progresses individuals report that they enjoyed the experience less over time yet continued to use it in increasing amounts. Motivational “wanting” or desire becomes uncoupled from hedonic “liking” over time.

This is not the case for ordinary “likes”. I really like pizza but if that was all I had to eat for several weeks I would enjoy it less and actively seek out some other food.

Contrary to earlier ideas it is now understood that dopamine does not mediate pleasure. Cellular sensitization changes in the reward pathway result in increased motivational drive uncoupled from hedonic pleasure. The drug creates a positive feedback loop. This drive persists into abstinence and at least partially explains craving and propensity for relapse in addiction recovery.

Florida man recently attempted a transatlantic crossing in this sea going hamster wheel. He got as far as 70 miles out before he was apprehended by the Coast Guard. An impressive display of motivation and courage.

Thank you for your consideration in reviewing this post. Comments, suggestions or feedback are welcome.

Jeff Kay 10/23 jeffk072261@gmail.com

Images and data obtained from sources freely available on the World Wide Web. No commercial or institutional interest. This post should not be considered medical or professional advice.

REFERENCES

Incentive Salience and the Transition

to Addiction

Mike J.F. Robinson, Terry E. Robinson and Kent C. Berridge

…………………………………………..

A computational substrate for incentive salience

Samuel M. McClure1, Nathaniel D. Daw2 and P. Read Montague1

1Center for Theoretical Neuroscience, Human Neuroimaging Laboratory, Baylor College of Medicine, 1 Baylor Plaza,

Houston, TX 77030, USA

2Computer Science Department, Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

TRENDS in Neurosciences Vol.26 No.8 August 2003

http://www.gatsby.ucl.ac.uk/~beierh/neuro_jc/McClure_Daw_Montague_03_IncentiveSalience.pdf

……………………………………………………………

Current Addiction Reports

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0202-2

ADOLESCENT/YOUNG ADULT ADDICTION (T CHUNG, SECTION EDITOR)

Neurobiology of Craving: Current Findings and New Directions

Lara A. Ray1,2 & Daniel J. O. Roche2

# Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

……………………………………….

https://www.jneurosci.org/content/21/23/9414

ARTICLE, Behavioral/Systems

Loss of Dopamine Transporters in Methamphetamine Abusers Recovers with Protracted Abstinence

Nora D. Volkow, Linda Chang, Gene-Jack Wang, Joanna S. Fowler, Dinko Franceschi, Mark Sedler, Samuel J. Gatley, Eric Miller, Robert Hitzemann, Yu-Shin Ding and Jean Logan

Journal of Neuroscience 1 December 2001, 21 (23) 9414-9418; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09414.2001

…………………………………………………

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0741832911005234

Volume 46, Issue 4, June 2012, Pages 317-327

Effects of alcohol on the membrane excitability and synaptic transmission of medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens

Vincent N. Marty, Igor Spigelman

………………………………………………..

Psychopharmacology (2007) 191:391–431 DOI 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x

REVIEW

The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience

Kent C. Berridge

……………………………………………….

Rats prone to attribute incentive salience to reward cues are also prone to impulsive action

Vedran Lovic, Benjamin T. Saunders, Lindsay M. Yager, and Terry E. Robinson*

Behav Brain Res. 2011 October 1; 223(2): 255–261. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.006.

…………………………………………………….

Disentangling pleasure from incentive salience and learning signals in brain reward circuitry

Kyle S. Smith kyless@mit.edu, Kent C. Berridge, and J. Wayne AldridgeAuthors Info & Affiliations

Edited* by Larry W. Swanson, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, and approved May 16, 2011 (received for review February 3, 2011)

June 13, 2011

108 (27) E255-E264

Leave a comment